Curator Notes

Pioneer sound artist Christian Marclay began manipulating gramophone records and creating time-based works using loops, skips and scratches on turntables as musical instruments in the 1970s. Working in sculpture, performance, video and other time-based media for nearly four decades, he incorporates strategies of collage, painting, appropriation, music composition, hip hop and DJing in his multimedia practice.

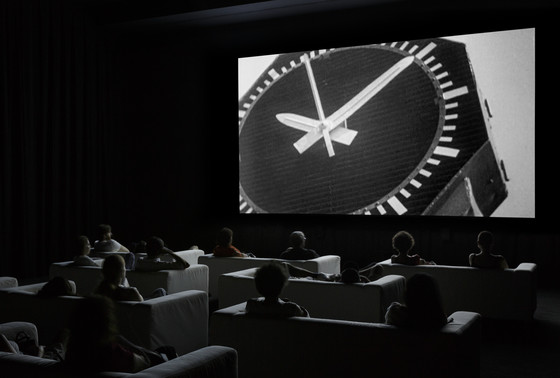

Since its premiere in London in October 2010, followed by its debut in New York February 2011, The Clock (2010) has been praised as a true masterpiece. Winner of the Golden Lion at the 54th Venice Biennale (2011), this twenty-four-hour single-channel montage is constructed out of moments in cinema and television history depicting the passage of time, in other words, scenes in which clocks and watches – “from clock towers to wristwatches and from buzzing alarm clocks to the occasional cuckoo” – appear. The Clock weaves together Marclay’s interests in collage and found visual and aural artifacts with his own roots in performance art. In this respect, the viewers become enmeshed in a durational performance piece.

The edited footage of clocks not only provides cues as to the role of time’s passage in the appropriated film narrative, but also serves as a functioning timepiece that marks the exact time for the viewer. When one sees The Clock at 1:15 pm, for example, the action (or inaction) in the clip will be taking place at the same moment for the viewer. Screened in a cinematic setting, it retains the rhythmic pulsations and tonal shifts typical of Marclay’s sound works but also plays with the viewer’s sense of expectation and surprise, drawing attention to time as a multifaceted protagonist in moving image. The Clock records the measure of time while also presenting a visual tapestry from, of, and about time in our frenzied twenty-first century existence, creating a conflation of tensions à propos the layered tempos of contemporary life. “If I asked you to watch a clock tick,” remarks Marclay, “you would get bored quickly, but there is enough action in this film to keep you entertained, so you forget the time, but then you’re constantly reminded of it.”

Marclay follows a long trajectory of artists interested in the history of cinema and the ways in which its footage or grammar can be appropriated and recontextualized. Experimental and documentary filmmakers have a long history since the dawning of the technology of using found or appropriated footage. The Russian filmmaker and scholar Jay Leyda devoted an entire book to the study of this method in Films Beget Films (1964) and connected the use of found footage in film to the collage techniques of Dadaism, Surrealism, and Constructivism, among other historical avant-gardes. An important, albeit much shorter, precedent to Marclay’s The Clock is Bruce Conner’s A Movie (1958), an experimental film which edits together clips from disparate sources, from stag to sports footage to mainstream melodramas, to create a meta-film. In A Movie’s complex building of cinematic time, Conner frustrates the viewer’s anticipation of a beginning, middle and end by throwing out all rules of linearity and narrative progression. Similarly, Marclay’s The Clock causes the viewer to ruminate on what David Velasco calls a film or television show’s “temporal grammar” in the way that Marclay “string(s) together this panoply of irrational times according to a rational tempo, he makes salient the idiosyncrasies of movie time,” (David Velasco in Artforum, February, 2011). The work pays homage to Andy Warhol’s eight-hour film, Empire (1964), in which the Empire State Building emerges from the white of sunset and goes dark immediately, the floodlights flicker for hours, mechanical notations such as lens flair, raindrops and camera bumps appear throughout, ending with near total darkness around 2:00 am. In its paradoxes of mechanical and metaphoric tension and humor, it also recalls Swiss artist duo Peter Fischli and David Weiss’s signature film The Way Things Go (1987), in which an overly-engineered 100-foot Rube Goldberg device performs a very simple task in the form of a series of chain reactions in twenty-nine minutes.

While more recent works by artists such as Douglas Gordon and Candice Breitz employ the use of found footage to comment on the limitations of authorship and artificiality of dramatic codes in a postmodern era, Marclay uses sampled segments to reformat our understanding of media’s discrete components. For example, in 2002, Marclay created Video Quartet, a montage that deftly created a musical composition out of individual clips from movies. While Video Quartet conveyed Marclay’s complex engagement with audio culture, and his ability to craft something wholly new out of foraged components, The Clock turns a collection of seemingly banal shots (of timepieces) into a compendium of cinema’s extraordinarily complex relationship to time and memory. (Christine Y. Kim, Associate Curator Contemporary Art)

More...