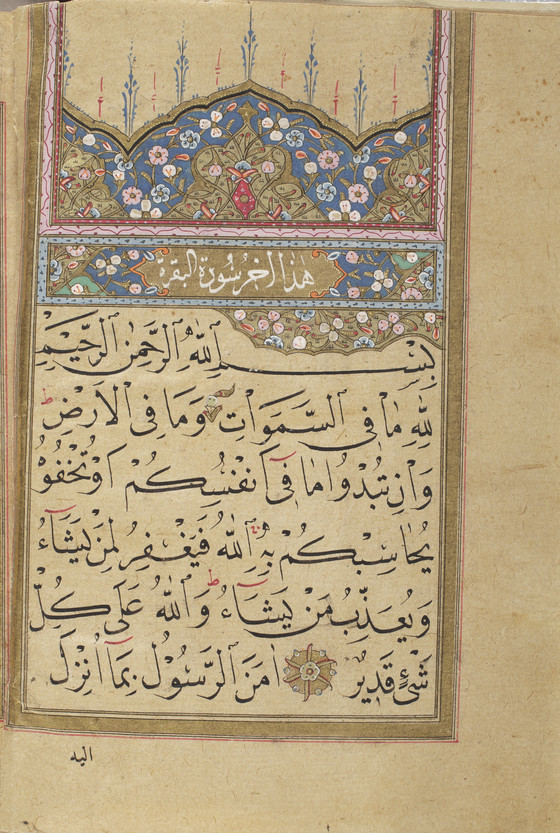

Muhammad ibn Sulayman, called al-Jazuli (d....

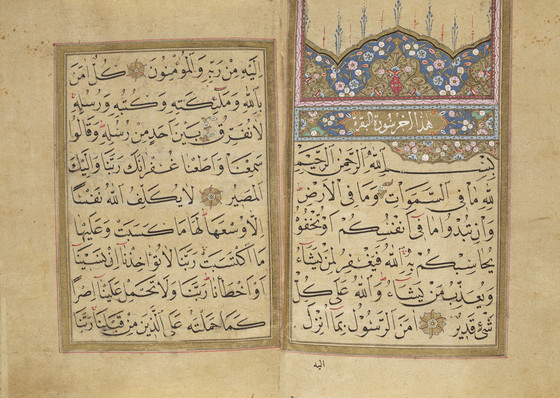

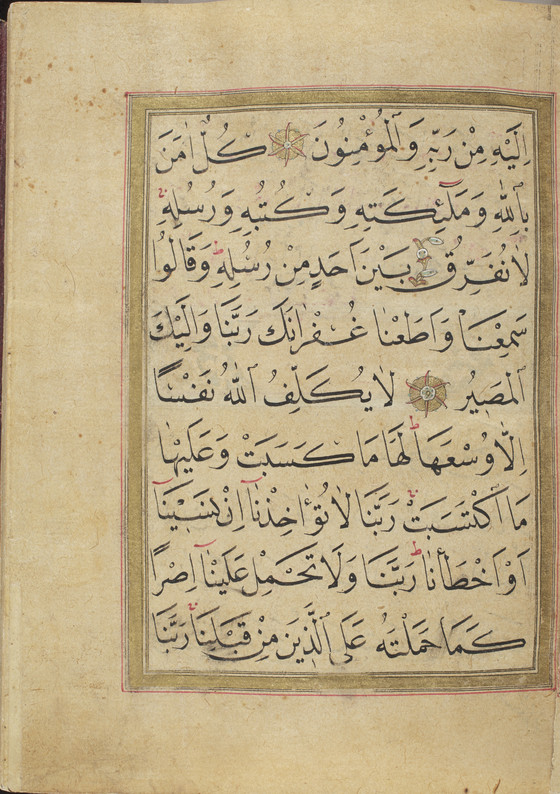

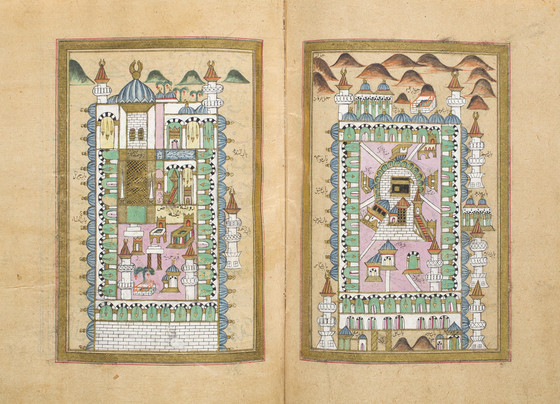

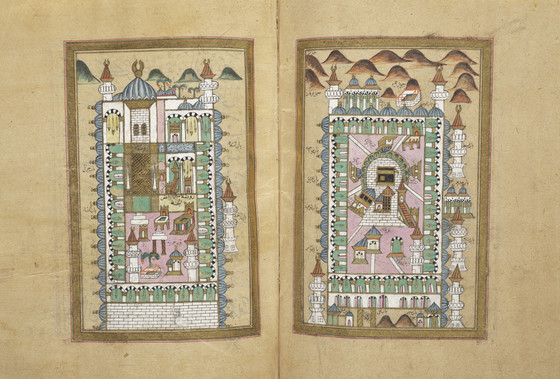

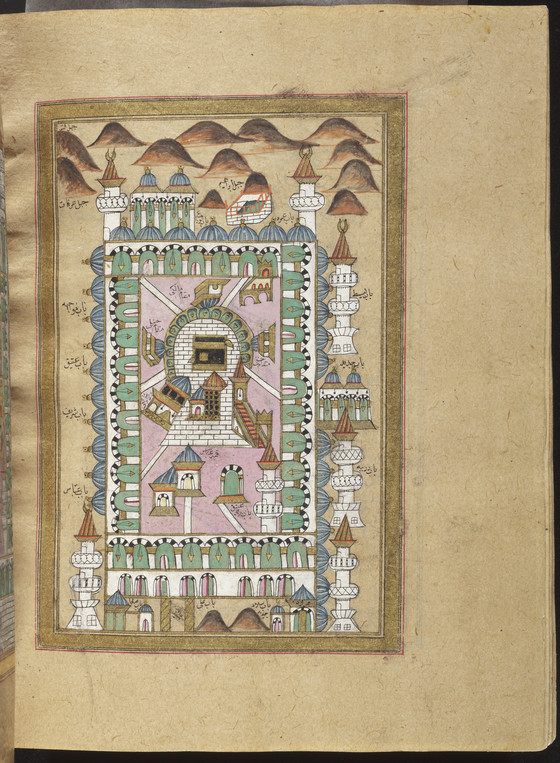

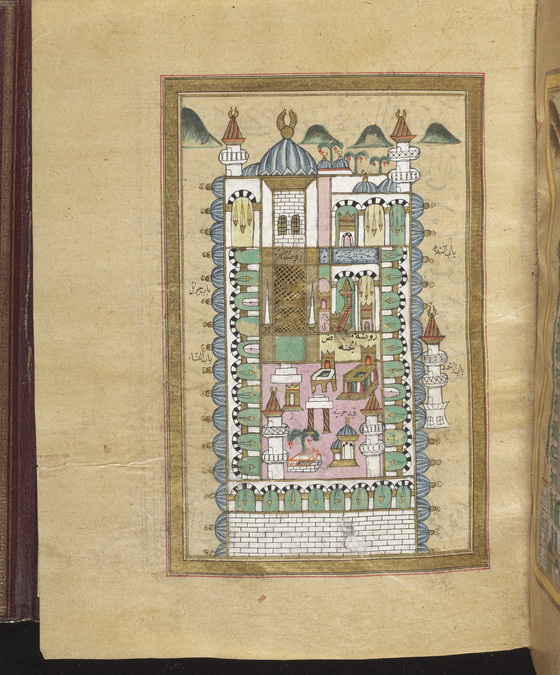

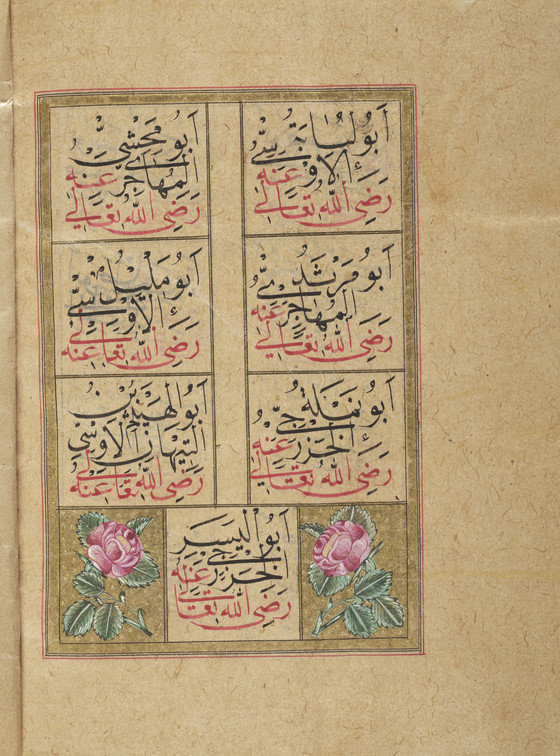

Muhammad ibn Sulayman, called al-Jazuli (d. 1465), was the author of a guide for Turkish pilgrims making the hajj to the holy shrines of Mecca and Medina, a journey required of each Muslim if at all possible. Numerous examples of such guides are known, dating mainly from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in Sunni communities. Usual features of such manuscripts, as here, are depictions of the Kaʼba in Mecca and the mosque and tomb of the Prophet in Medina, among other shrines. Labels often accompany the images as a way of orienting the pilgrim during their travels or prayers.

While this guide could prepare an individual for pilgrimage, the manuscript remained important to many readers long after their journeys. Some served as mementos of the pilgrimage experience, and others allowed armchair travelers to visualize the holy sites from afar in a more intimate form of worship. Additionally, this collection of prayer-blessings lends itself to devotional recitation in groupings of 8, 4, and 2 prayers each. Worshippers sometimes also used their paintings in more tactile acts of devotion that activated the holy properties of these images. Many manuscripts of the Dala'il al-Khayrat bear traces of owners kissing, touching, and rubbing their faces or fingers on the images of these holy sites. In fact, some manuscripts experienced such frequent use that they suffered significant losses in their pigments as a result. A close look at the painting of Mecca in this manuscript reveals a prominent smudge in the shape of a fingerprint on the upper left entrance to the courtyard of the Masjid al-Haram, with another fingerprint smudge on the bottom wall to the holy sanctuaries in Madina on the left. While the exact reasons could vary, it is posited that some believers used these works as talismanic objects in order to obtain forgiveness for minor sins, protection, blessings, cures, or other forms of intercession that would spiritually connect the viewer to the holy sites, the Prophet Muhammad, and, of course, God.

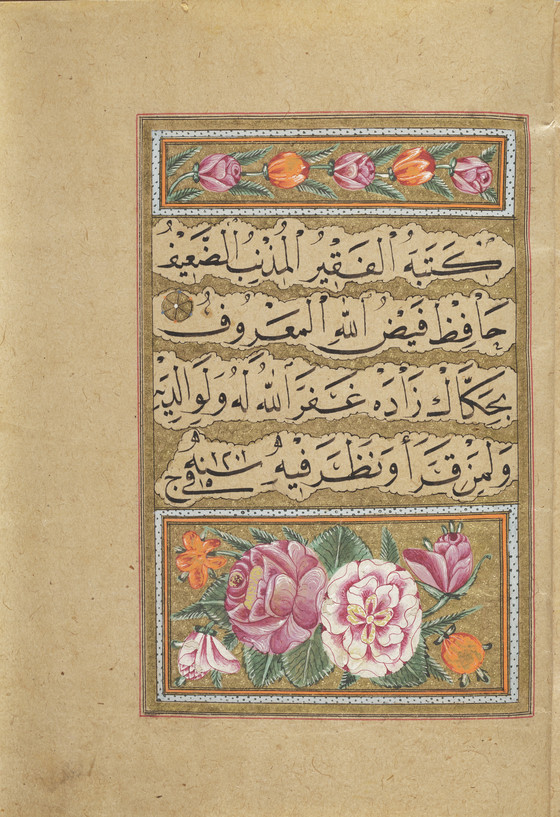

By this period, the paintings of Mecca and Medina in al-Jazuli’s text could encompass naturalistic single-perspectival views that followed the latest Europeanizing trends, to multi-perspectival ones that had a much longer history in Ottoman painting. This bi-folio opening of the two cities follows the latter approach, which raises the hinter portion of courtyards and accompanying buildings so that the viewer could easily behold all of the key pilgrimage stations at once. In contrast, the illuminated program incorporates hyper-naturalistic depictions of roses on golden grounds as the headers and footers to each section. This manuscript thus combines old and new modes of painting within the same visual program.

More...