...

Kunga Tashi reigned as abbot of the Sakya monastery from 1688 until his death in 1711. As no biography has been found, little is known about his life. Hence, this painting with its identifying inscriptions is the most complete record of his activities.

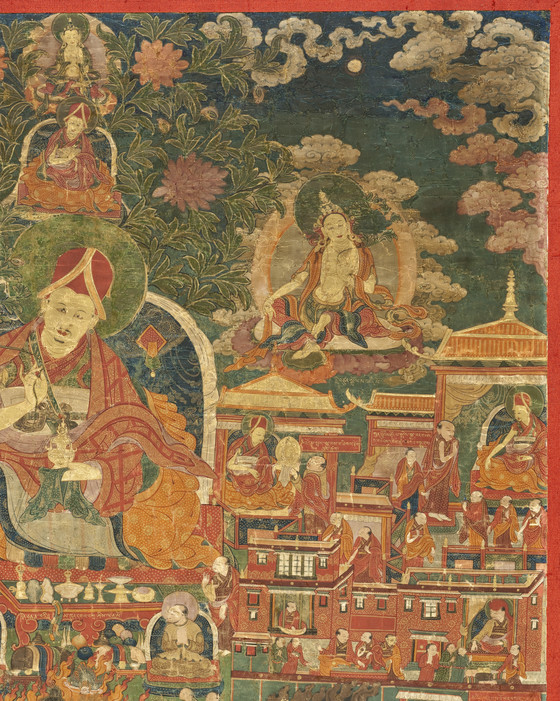

Kunga Tashi, the central figure in the painting, is depicted wearing the distinctive red hat of a Sakyapa hierarch. In his left hand, he holds the flowering Vase of Immortality, associated with the Dhyanibuddha of Unmeasured Life, Amitayus. In his right hand, he holds a lotus stalk surmounted by the manuscript and flaming sword of Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom. Kunga Tashi orders his treasurer, to his left, to have a golden statue made and a temple built.

Directly below these scenes, Kunga Tashi offers gems to the god of wealth Kubera while accompanied by the lay donor who funded his religious undertakings. Immediately to the left Kunga Tashi lectures in the temple where monks were tested in theology and logic. In the cavalcade in the bottom left Kunga Tashi is depicted traveling [?] to perform a religious ceremony near the source of the Yangtze River in eastern Tibet. Above the procession he orders the repair of the Samtin monastery and the great temple, Lhakhang Chenmo, one of the important monasteries at Sakya.

The Sakyapa hierarch depicted directly above Kunga Tashi represents either his father, Sonam Wangchök (1638–85), or another great Sakyapa teacher. The two monks who commissioned this painting are seated below Kunga Tashi and, according to the inscription, are "praying to obtain his favor." The presence of Manjushri above Kunga Tashi’s right shoulder and Tara, the female Bodhisattva of Compassion, above his left symbolize his Enlightenment. The Buddha Vajradhara, who is considered to be the source of Sakyapa teachings, is depicted at the top center. Below the throne, Mahakala as the Lord of the Pavilion, the tutelary (protective) deity of the Sakyapa, is flanked by two forms of the fierce female deity, Palden Lhamo.

This painting exemplifies the stylistic changes that spread throughout central Tibet during the late 17th century. Traditionally Sakyapa paintings were strictly symmetrical. Influenced by Chinese art, Tibetan artists began to incorporate landscape elements into their paintings and to create more active compositions. Kunga Tashi is asymmetrically posed, and the events of his life are identified by inscriptions and divided by thin areas of landscape. Each portion of the story is descriptively portrayed within an architectural setting, rather than being subsumed by just the principal figures.

More...