Architectural Element

Please log in to add this item to your gallery.

View comments

No comments have been posted yet.

Add a comment

Please log in to add comments.

Please log in to add tags.

* Nearly 20,000 images of artworks the museum believes to be in the public domain are available to download on this site.

Other images may be protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights.

By using any of these images you agree to LACMA's Terms of Use.

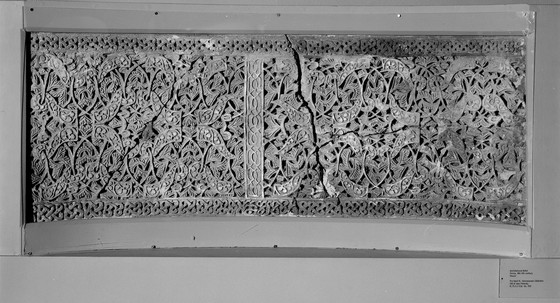

Architectural Element

Spain, Granada, late 13th-early 14th century

Stucco

Stucco, carved, traces of paint

51 x 18 1/2 in. (129.54 x 46.99 cm)

The Nasli M. Heeramaneck Collection, gift of Joan Palevsky (M.73.5.2)

Not currently on public view