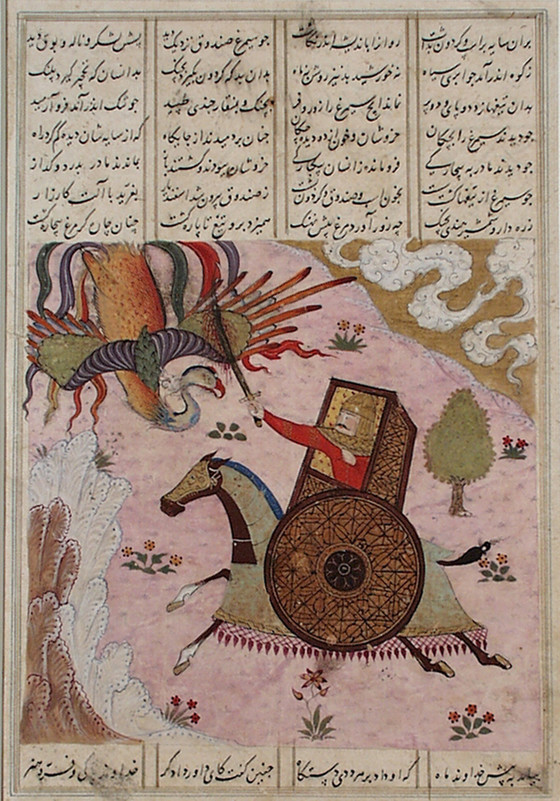

Isfandiyar Attacks the Simurgh from an Armored Vehicle, Page from a Manuscript of the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Firdawsi

Please log in to add this item to your gallery.

View comments

No comments have been posted yet.

Add a comment

Please log in to add comments.

Please log in to add tags.

* Nearly 20,000 images of artworks the museum believes to be in the public domain are available to download on this site.

Other images may be protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights.

By using any of these images you agree to LACMA's Terms of Use.

Isfandiyar Attacks the Simurgh from an Armored Vehicle, Page from a Manuscript of the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Firdawsi

Iran, Shiraz, circa 1485-1495

Manuscripts; folios

Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

8 7/8 x 6 in. (22.54 x 15.24 cm)

The Nasli M. Heeramaneck Collection, gift of Joan Palevsky (M.73.5.410)

Not currently on public view