Curator Notes

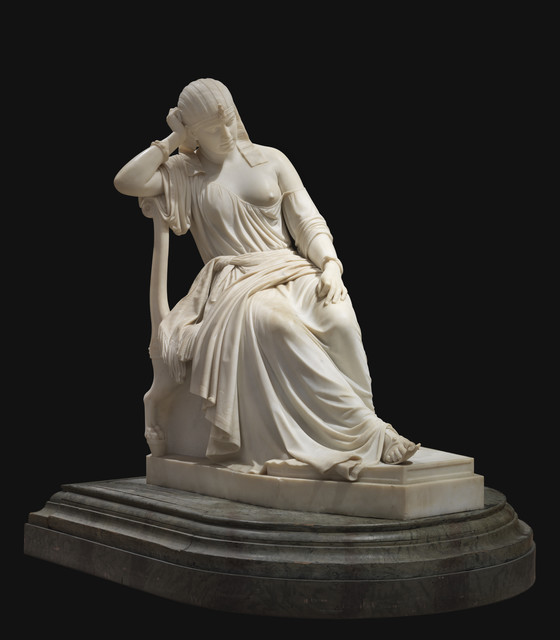

Cleopatra made Story’s reputation and set the standards for the second phase of American neoclassical sculpture. Story had planned to begin a compositional study for it during the winter of 1856-57 but only started the clay model during the winter of 1858. The carving of Cleopatra in marble was not completed until December 1860, but the statue was inscribed with only an 1858 date to commemorate the commencement of work.

When he could had not attract any buyers for the work over the next several years, Story contemplated abandoning the profession. Pope Pius IX sent, at his expense, Cleopatra and Story’s Libyan Sibyl, 1860 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) to the 1862 International Exhibition in London along with several other sculptures by artists residing in Italy. Cleopatra was an immediate success, receiving favorable reviews from several newspapers and periodicals, including the London Athenaeum, which rated it, along with the Libyan Sibyl, as the most important sculpture in the exhibition. As a result, Story found a buyer for Cleopatra, a Mr. Morrison, a wealthy, provincial Englishman, who paid him three thousand pounds for it. The sculpture remained in the family, lost to public attention until 1978, when it was bought by the museum.

The museum’s marble is the only example of the first of three versions created by the sculptor. About 1863-64 Story created a second version by slightly altering details of the original design. Four marble examples of this second version were made in life size, each dated at the time of its sale (Daniel Grossman, Inc., New York, 1865; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1869; unlocated, formerly collection of Count Palffy, Paris, 1877; High Museum of Art, Atlanta, 1878). The one in the Metropolitan Museum of Art is the best known example of this second version. Later, in 1884, Story revised his idea a third time to design a reclining Cleopatra; it is not known if this version was ever realized in marble.

The fame of Cleopatra is due not only to its reception in 1862 but also to the frequency with which the Metropolitan Museum’s sculpture has been discussed and reproduced in the literature on Story; the best-known example, it has often been mistaken for the first version. The difference between the Los Angeles Museum’s and the Metropolitan Museum’s sculptures are subtle yet significant. They represent the sculptor’s reinterpretation of the theme and his turn to a more naturalistic style, one that was favored by the second generation of neoclassical sculptors. Julian Hawthorne discussed the artist’s quandary over the gesture of Cleopatra’s left hand:

I remember very well the statue of Cleopatra while yet in clay . . . . Cleopatra was substantially finished, but Story was unwilling to let her go, and had no end of doubts as to the handling of minor details. The hand that rests on her knee-should the forefinger and thumb meet or be separated? If they were separated, it meant the relaxation of despair; if they met, she was still meditating defiance or revenge. After canvassing the question at great length with my father [Nathaniel Hawthornel, he decided that they should meet; but when I saw the marble statue in the Metropolitan Museum the other day I noticed that they were separated.

Hawthorne obviously saw the model for the first version in the studio: in the Los Angeles marble the thumb and forefinger are touching. Story exaggerated the relaxed posture of the figure and changed the drapery in the second version. In the Los Angeles Cleopatra the left breast is partially exposed, with the drapery hanging in an unnatural but decorous manner; in the Metropolitan Museum’s example Cleopatra’s left breast is fully exposed, her garment falling from her shoulder more naturally. Other differences in the details between the two versions might be attributed to the growing interest in the Near East that took place in Europe and America during the second half of the nineteenth century. In the Metropolitan Museum’s figure Story gave the Egyptian queen a slightly more African physiognomy, perhaps to suggest an Eastern sensuality. Story also changed the details of the base from a simple, classical, rectangular design to one with Eastern arches.

The exoticism of Cleopatra is most obvious in the figure’s jewelry and demonstrates just how typical of the nineteenth century the sculpture is. During the mid-1860s the artist had the opportunity of visiting in Paris an exhibition of ancient Egyptian jewelry and other artifacts. Although Story was praised for the authenticity of the Eastern jewelry, Cleopatra’s accoutrements were a modern fabrication based on some familiarity with, but not an accurate understanding of, ancient artifacts. While Story’s figure wears the Egyptian nemes (headcloth), the cloth is not flat as in those worn by the Ptolemaic pharaohs nor is the uraeus (cobra headdress) positioned correctly. Story’s Cleopatra wears two bracelets, a snake band whose ends do not spiral in the same configuration as ancient jewelry, and a bracelet of authentic scarabs in a Victorian setting. The reworking of ancient motifs is also apparent in the chair. In his fascination with the decorative detail of other eras Story was a typically Victorian artist. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Marble Faun (1860) was a fictionalized account of Story’s creation of the first version of Cleopatra. It and the later publication of the writer’s journals were partly responsible for the sculpture’s reputation. Hawthorne, who was a friend of Story’s in Rome, witnessed the creation of the statue almost from the start. Visiting Story on February 12, 1858, only fourteen days after he had commenced work on the sculpture, Hawthorne wrote in his journal, "The statue of Cleopatra ... is a grand subject, and he is conceiving it with depth and power . . . . He certainly is sensible of something deeper in his art than merely to make nudities and baptize them by classic names." The type of subject matter Story preferred might have been encouraged by his friendship with Hawthorne, for like the author, Story was intrigued by heroes caught in intense psychological drama. Unlike other American neoclassical sculptors, Story was fascinated with mythical and historical heroines, such as Medea and Delilah, whose fates were determined by their personalities. Cleopatra was the first of several statues he made of such women. Story often depicted his heroines seated and brooding, inspired by the powerful seated prophet figures of Michelangelo, whom he greatly admired.

Hawthorne’s admiration of Story’s abandonment of the classicized representation in favor of a more real, even "terribly dangerous woman," led him to the story of the sculptor Kenyon in The Marble Faun ([Chicago: Homewood, 1861, pp. 101-3):

"My new statue!" said Kenyon . . .

He drew away the cloth that had served to keep the moisture of his clay model from being exhaled. The sitting figure of a woman was seen. She was draped from head to foot in a costume minutely and scrupulously studied from that of ancient Egypt, as revealed by the strange sculpture of that country, its coins, drawings, painted mummy-cases, and whatever other tokens had been dug out of its pyramids, graves, and catacombs. Even the stiff Egyptian head-dress was adhered to, but had been softened into a rich feminine adornment . . . . Cleopatra sat attired in a garb proper to her historic and queenly state . . . .

A marvelous repose-that rare merit in statuary . . . was diffused throughout the figure. The spectator felt that Cleopatra had sunk down out of the fever and turmoil of her life, and for one instant . . . had relinquished all activity . . . . It was the repose of despair.

The face was a miraculous success. The sculptor had not shunned to give the full, Nubian lips, and other characteristics of the Egyptian physiognomy. His courage and integrity had been abundantly rewarded; for Cleopatra’s beauty shone out richer, warmer, more triumphantly beyond comparison, than if, shrinking timidly from the truth, he had chosen the tame Grecian type. The expression was of profound, gloomy, heavily revolving thought.

In a word, all Cleopatra-fierce, voluptuous, passionate, tender, wicked, terrible, and full of poisonous and rapturous enchantment-was kneaded into what, only a week or two before, had been a lump of wet clay from the Tiber.

"What a woman is this!" exclaimed Miriam.

More...

About The Era

After the Jacksonian presidency (1829–37), the adolescent country began an aggressive foreign policy of territorial expansion, exemplified by the success of the Mexican-American War (1846–48). Economic growth, spurred by new technologies such as the railroad and telegraph, assisted the early stages of empire building. As a comfortable and expanding middle class began to demonstrate its wealth and power, a fervent nationalist spirit was celebrated in the writings of Walt Whitman and Herman Melville. Artists such as Emanuel Leutze produced history paintings re-creating the glorious past of the relatively new country. Such idealizations ignored the mounting political and social differences that threatened to split the country apart. The Civil War slowed development, affecting every fiber of society, but surprisingly was not the theme of many paintings. The war’s devastation did not destroy the American belief in progress, and there was an undercurrent of excitement due to economic expansion and increased settlement of the West.

During the postwar period Americans also began enthusiastically turning their attention abroad. They flocked to Europe to visit London, Paris, Rome, Florence, and Berlin, the major cities on the Grand Tour. Art schools in the United States offered limited classes, so the royal academies in Germany, France, and England attracted thousands of young Americans. By the 1870s American painting no longer evinced a singleness of purpose. Although Winslow Homer became the quintessential Yankee painter, with his representations of country life during the reconstruction era, European aesthetics began to infiltrate taste.

More...

During the postwar period Americans also began enthusiastically turning their attention abroad. They flocked to Europe to visit London, Paris, Rome, Florence, and Berlin, the major cities on the Grand Tour. Art schools in the United States offered limited classes, so the royal academies in Germany, France, and England attracted thousands of young Americans. By the 1870s American painting no longer evinced a singleness of purpose. Although Winslow Homer became the quintessential Yankee painter, with his representations of country life during the reconstruction era, European aesthetics began to infiltrate taste.

Label

Exhibition Label from Masterpiece in Focus, 2007

The lover of both Julius Caesar and Marc Antony, Cleopatra was Egypt's last pharaoh and defended her kingdom until the bitter end: rather than surrender Egypt to the Romans, she deliberately succumbed to the bite of a poisonous asp. William Wetmore Story captured the drama of Cleopatra's legendary powers of seduction and her death in his masterpiece, which he created in clay in Rome during the winter of 1858 and then had carved in marble in 1860.

Story conveyed a powerful sense of character and narrative through his subject's facial expression, pose, and costume details - all of which marked a striking departure from the more reserved traditions of contemporary neoclassical sculpture. From her pensive countenance, draping gown and sash, snake and scarab bracelets, cobra headdress, and anxious hand gesture, Story expressed the very moment that Cleopatra confronted her passions and her fate.

LACMA's Cleopatra - the first of three versions Story created of the queen - is the sculpture that single-handedly made Story famous. In 1862 this Cleopatra was exhibited at the International Exhibition in London. It was lauded in reviews, such as in the esteemed literary magazine Athenaeum, which cited Cleopatra as the most important sculpture in the exhibition.

More...

Bibliography

- About the Era.

- Price, Lorna. Masterpieces from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1988.

- Fort, Ilene Susan and Michael Quick. American Art: a Catalogue of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art Collection. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1991.

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art. New York: Thames and Hudson, 2003.