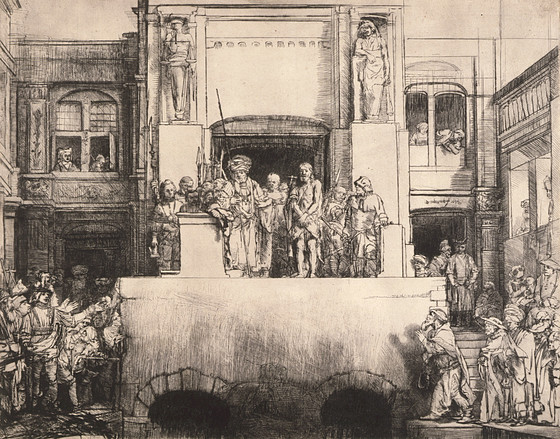

In 1655 Rembrandt finished the last of eight states of this etching of Christ's judgment. The first five states of the print include a milling crowd in the foreground below the central group....

In 1655 Rembrandt finished the last of eight states of this etching of Christ's judgment. The first five states of the print include a milling crowd in the foreground below the central group. In the sixth state, Rembrandt burnished out this crowd, replacing it with two arches flanking the figure of a river god. As a result, the somber composition, seen here in the seventh state, is organized almost entirely by the prominent architecture separating and enclosing three major groups. The curious townsfolk (left and right) represent disorder; the officials and soldiers around Christ symbolize an abstract, implacable justice. Individual figures are confined to windows, as the carved figures of Justice and Prudence are confined to their niches.

Both this subject and its presentation in an architectural setting had long been popular in northern Europe. The shallow, stagelike composition, with its varied levels and central platform, provided Rembrandt the opportunity to depict a large crowd of people. They are clothed in the anachronistic combination of exotic and contemporary costume that appears frequently in his biblical compositions. The variety of poses and costumes tempers the powerful symmetry of the architecture.

A shadowy central arch frames the richly dressed Pilate, who points to Christ, physically powerless among his oppressors. Rembrandt's very human depiction of the Savior occurs often in his work. The public setting of the judgment connects the image to the contemporary European practice of sentencing convicted persons in the open, before crowds.

New Hollstein 290, state viii/viii

More...