Among the world's most famous artifacts, the Ardabil carpet and its mate in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, are products of the great flowering of the arts, particularly those of textile an

...

Among the world's most famous artifacts, the Ardabil carpet and its mate in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, are products of the great flowering of the arts, particularly those of textile and the book, under the Safavid rulers of Iran. The site of Ardabil in northwest Iran was sacred to these Shiite rulers; tradition holds that both carpets were presented to the shrine there as royal gifts, and current scholarship confirms this. Magnificent gifts to this shrinean entire library of sacred and secular Islamic texts, a treasure of Ming dynasty porcelain, as well as lamps, silk brocades, and candlesticksconfirm the esteem in which these princes held it.

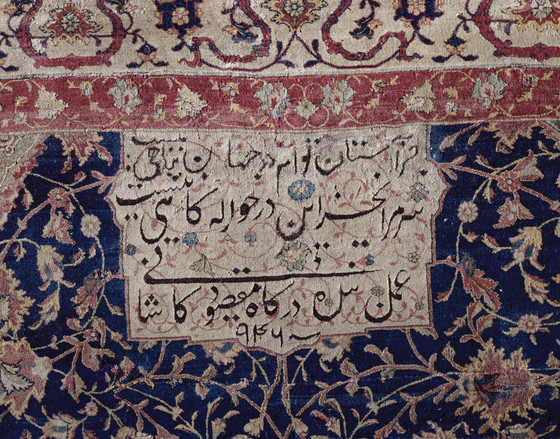

Both versions of the carpet are signed and dated early in the reign of Shah Tahmasp I, a renowned patron of the arts, and were probably made in Tabriz, a site of royal textile manufacturing (r. 1524 - 1578). This carpet contains 35,000,000 knots and probably took eight to ten craftsmen more than three years to complete.

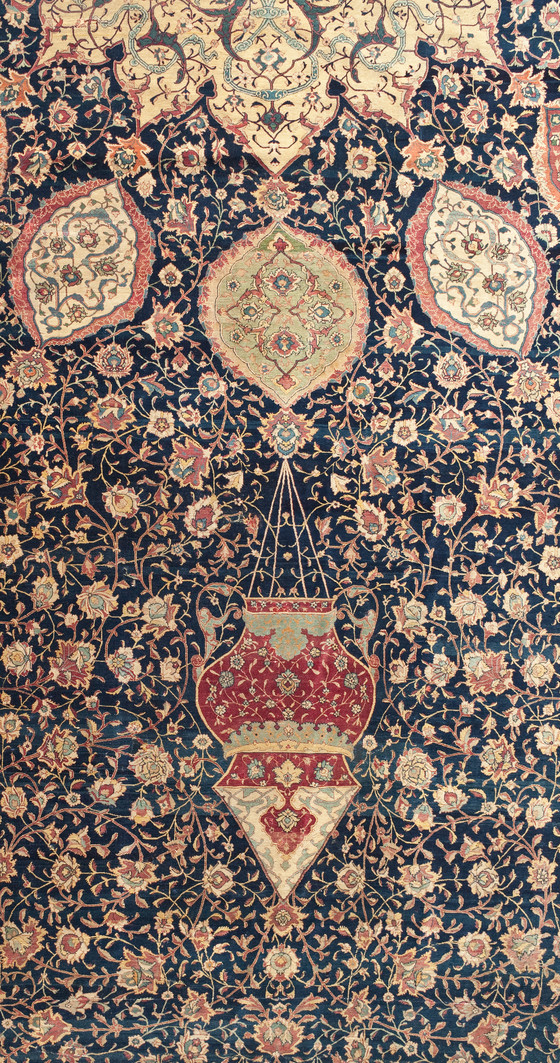

The carpet's subtle design, dominated by a large central medallion, is typical of Tabriz work. The overall scheme seems largely abstract, but individual motifs have figural sources. Sixteen ogival shapes surround the central sunburst medallion, and a pair of mosque lamps in the vertical axis flank the design. The undulating border forms derive from Chinese cloud-band motifs. Over the shimmering indigo surface is a meticulously balanced, if botanically improbable, meander of blossom-laden vines. The blossoms are a typical Sasanian lotus palmette crossed with a Chinese peony, some in full bloom and others barely emerging from buds. At the center of the great medallion is a roundel shaped like a geometrical pool of the kind that still exists in the Islamic gardens of the Alhambra in Spain. Such pools were essential to both the design and concept of Persian gardens, an art form that evoked the pleasures of paradise for the Muslim believer.

Identical inscriptions are woven into each of the carpets: "Except for thy haven, there is no refuge for me in this world: / Other than here, there is no place for my head. / Work of a servant of the court, Maqsud of Kashan, 946." This evocation of a heavenly refuge is particularly appropriate for a work of art that recalls the abundance and fertility of the garden, the most powerful symbol of physical and spiritual peace in the Muslim world.

More...