Until 1893, when historian Frederick Jackson Turner declared the western frontier closed, the nation had perceived itself as an ever-expanding geographical entity....

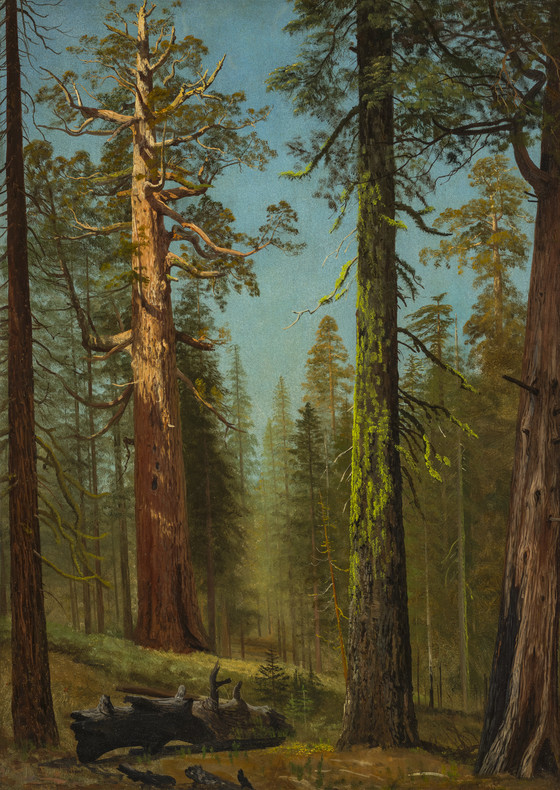

Until 1893, when historian Frederick Jackson Turner declared the western frontier closed, the nation had perceived itself as an ever-expanding geographical entity. The frontier moved westward as the forests of the Adirondacks, Catskills, and Alleghenys of the eastern seaboard were cleared and inhabited. Euro-American settlers pushed across the continent, through the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains, until they reached the Pacific Ocean. Although the actual travels of explorers, government surveyors, and settlers can be traced through the changing locales in landscape paintings, such depictions were to a certain extent idealizations. In the romantic-realist tradition of the Hudson River school, artists emphasized the primitive character of the wilderness and presented the newly cultivated farmlands as agrarian oases divinely blessed by rainbows and golden mists.

Artists and writers promoted nature as a national treasure. However, the wealth of the land was measured in commercial as well as aesthetic terms. Railroads and axes appear in paintings as symbols of civilization, yet they also were instruments of destruction.

According to some, the nation was preordained by God to span the continent from coast to coast. In 1845 the editor John O’Sullivan coined the term “Manifest Destiny,” referring to the country’s duty to annex western territories and exploit their resources. The same railroad tycoons and land developers who promoted such a policy also commissioned artists to paint epic scenes of the American landscape. Manifest Destiny ignored the rights of Native Americans, who had inhabited the region long before European settlers arrived. Consequently, it is not surprising that Native Americans are absent from, or stereotyped in, most of the painted views of the land they called their home. The West seen in most nineteenth-century paintings was largely one of the imagination.

More...