Cabinets took Europe by storm in the middle of the 16th century, and remained furniture makers’ most prestigious product throughout the 1600s. This was largely due to their ingenious decoration and their costly and rare materials. Cabinets with multiple drawers derived from the Spanish escritorio or papelera. This furnishing type was originally used to store papers, and eventually evolved to enclose all sorts of collectibles and valuable possessions. Traded as works of art, cabinets often featured in Spanish still life paintings alongside other precious items from across the globe.

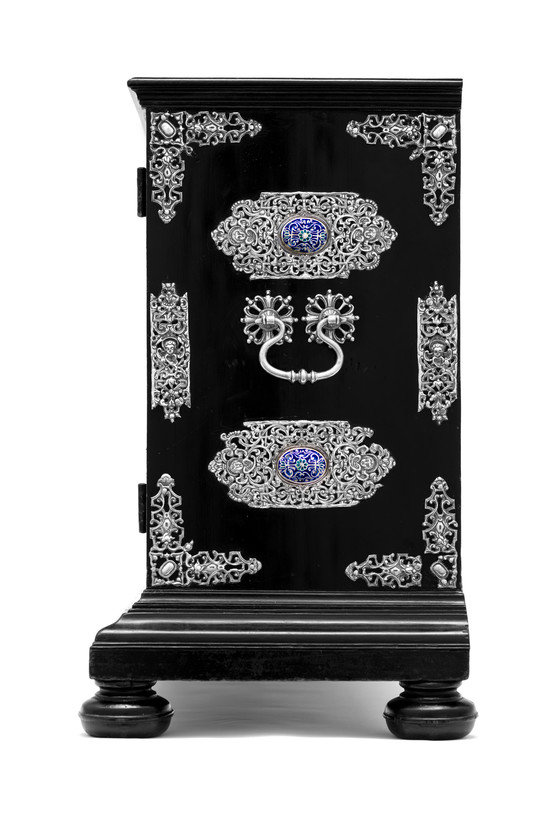

Fine examples, many exported across Europe, were produced in Antwerp, which is where this cabinet was most likely created. Ebony was a costly, tropical wood imported mostly from Southeast Asia that became an immediate sensation in Europe, and was widely imitated. This ebonized cabinet opens up to reveal a set of drawers bedecked with intricately cast and chased openwork silver applications. The exterior is decorated with a multiplicity of silver ornaments, enhanced with vivid blue and green champlevé enamel work, that mirror one another and cover the piece like a precious skin, creating an entrancing effect.

An interior medallion bears a “talking” inscription in Spanish that reads: “Me fiso Enjoyar / Mi Sor. EXMO.. / D. Melchor / Portocarrero / Lasso de la Vega / Conde de la Monclova” (I was bejeweled at the behest of my master His Excellency Don Melchor Portocarrero Lasso de la Vega, Count of Monclova). The Count of Monclova had a distinguished military career serving the Spanish crown. In 1658 he lost an arm in a calamitous battle against the French, earning him the moniker “Silver Arm” (Brazo de plata). As a reward for his loyalty, he was appointed viceroy of Mexico from 1686 to 1688, and of Peru (where he died) from 1689 to 1705. In Lima, he faced the daunting job of rebuilding the city after the devastating earthquake of 1687. A profoundly religious man, during his long tenure as Peru's governor he supported the establishment of several convents and oversaw the construction of numerous churches.

Silver was closely associated with empire building in the early modern world. In 1545, the Spaniards stumbled upon the world’s richest silver deposit, the Cerro Rico or “Rich Hill” of Potosí (in present-day Bolivia), which fueled a veritable silver bonanza and drove the global economy for nearly three centuries, turning Spain into the envy of the world. Silver objects fulfilled both practical and symbolic functions. They were used to embellish churches and the homes of the elite and to signal the proverbial wealth of viceregal society.

It is not surprising that when the newly appointed viceroy arrived in Lima, possibly carrying the cabinet as part of his personal household items, he would have had it enhanced with Peru’s legendary

silver by local master silversmiths. The profusion of winged angels tucked in the silver strapwork, was a motif used across a range of Peruvian objects. Their abundance might suggest that the viceroy gifted the cabinet to a convent he supported, or that he commissioned it for someone he cherished as an outward symbol of his esteem. (The cabinet does not feature in the viceroy’s probate inventory following his death.)

Whatever the case, everything about this piece is aimed at creating an overwhelming first impression, revealing the virtuosity with which it was embellished, its costly materials, and the role of the viceroy in its creation. The work is a brilliant example of how objects could be altered and reactivated as they moved about the world.

Ilona Katzew, Curator and Department Head, Latin American Art, 2023