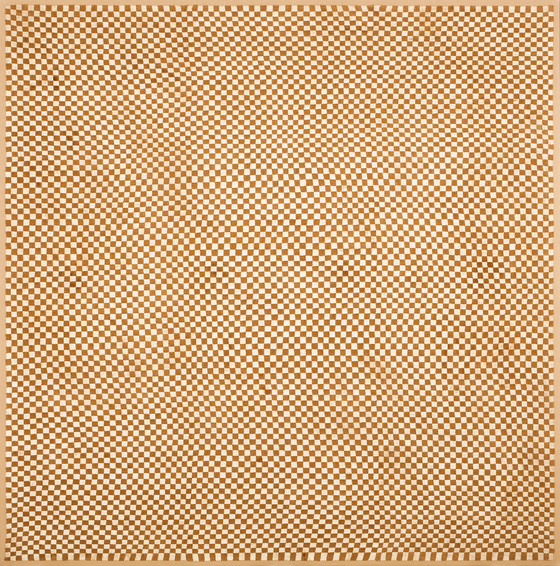

The austere geometry of the checkerboard, rendered in a singular, virtuoso weaving technique, indicates that this impressive textile was made to be displayed in a prestigious political or religious co...

The austere geometry of the checkerboard, rendered in a singular, virtuoso weaving technique, indicates that this impressive textile was made to be displayed in a prestigious political or religious context. Textiles, the most important commodity in the ancient Andean world, were an integral part of all tribute, taxation, religion, political ceremony, birth, marriage, and death. The powerful visual impact of this cloth mosaic in its reductive color range is heightened by the metaphorical significance of the brown and white squares—symbolizing the ancient Andean belief in dynamic dualism, reciprocity, and complementarity between cosmic forces and the natural realm.

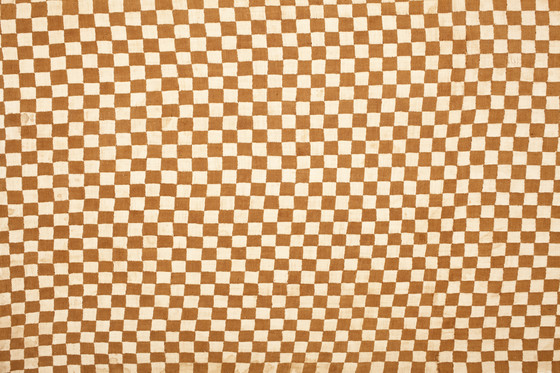

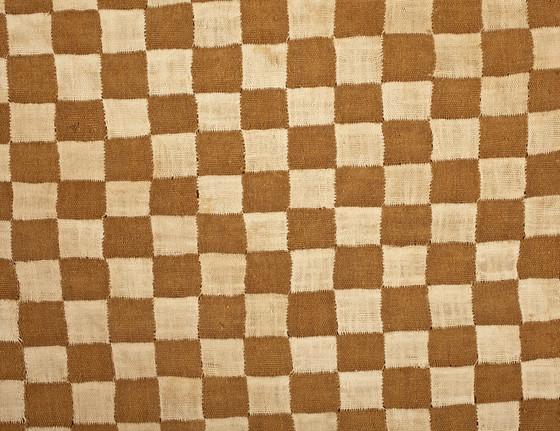

Woven in a highly meticulous technique in which neither warps nor wefts extend across the entire cloth, the textile was created with “scaffold” threads (which were later removed) that formed a temporary grid upon which to weave each miniscule square separately. The fabric was assembled by the intensive process of interlocking the warps and wefts of each adjacent square—forming a single cloth from the sum of many parts. In the history of world textiles, the technique of discontinuous warp and weft was practiced only in the Andes.

Dynamic dualism, represented in the textile by juxtaposed light and dark squares, was a fundamental principal of ancient Andean thought. In this cosmological principle the universe was organized of contrasting but complementary opposites, and balance was attained by the interchange between the two. Balanced, harmonious existence was achieved through reciprocity, or interdependence of all human activity; in the harsh Andean environment, life was established on reciprocal relationships between family, co-workers, the administration, and the ruler, and on relationships that extended over the disparate geographies from the jungles of eastern Peru, to the Andes, to the dry desert coast. Reciprocity, symbolized by this intricate, composite textile, is expressed in the interweaving of ten thousand fully finished squares—independent, yet interdependent—suggesting unity of the individual and the community.

An aesthetic object that signifies universal order, this textile is based on the same grid matrix woven into Andean textiles over a span of two thousand years. Remarkably, such an extraordinary example of the weaver’s art, more than 450 years old, could be mistaken for an artwork produced in the last half of the 20th century. For LACMA, with holdings in art from all over the world, this stunning Inka textile is a quintessential example of the aesthetic bond that unites time, space, and cultural diversity. (Kaye Spilker, Curator Costume and Textiles)

More...