Curator Notes

Bamboo has long been treasured by scholars in East Asia as one of the Four Gentlemen, a group of plants that also include plum, orchid, and chrysanthemum and symbolize the principals of a virtuous literatus. Each plant has distinctive characteristics that represent the qualities that scholar-officials wished to cultivate. The plum, for example, endures the freezing weather to blossom first in the early spring, symbolizing a scholar’s unyielding strength during difficulty. The orchid has a mild fragrance that can travel a great distance, suggesting the virtue of a scholar will influence broadly. The chrysanthemum, which blooms in the cool weather of autumn when other flowers wither, also has a mild fragrance and long-lasting, single-color flowers, signifying that one who endures obstacles will find a good outcome. Bamboo symbolizes loyalty and uprightness because it is flexible – it bends easily but does not break – and it grows upward in straight shoots.

In painting, the subject of the Four Gentlemen was popular not only because it was highly symbolic to the literati, or amateur scholar-artists, but also because artists could display their technical virtuosity. To paint bamboo, the artist must maneuver the brush in a variety of delicate and occasionally spontaneous brushstrokes, including straight lines, angular and soft turns, and circular strokes in all directions. The artist must master the versatile brush, including how much pressure to apply and how quickly to move. (In East Asia, artists often use the phrase “hitting bamboo” to describe the process of painting bamboo, due to the spontaneity required for the brushstrokes.)

Bamboo has been a popular subject for centuries among writers, scholars, and painters in East Asia. In Korea, bamboo appears in paintings in the middle Goryeo dynasty. By the fourteenth century, during the transition between the Goryeo and Joseon periods, bamboo as a subject increased in popularity with the importation and circulation of paintings from the Chinese Yuan dynasty (1279-1368). Bamboo paintings by Chinese masters including Wen Tong (1019-1079), Su Shi (1037-1101), Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322), and Li Kan (1245-1343) were introduced to Korean literati painters at that time.[1] Bamboo later flourished as a popular motif of the literati during the Joseon period, because the literati enjoyed support from the official Confucian state. Not limited to painting, the bamboo motif also appeared on ceramics and in the decorative arts.

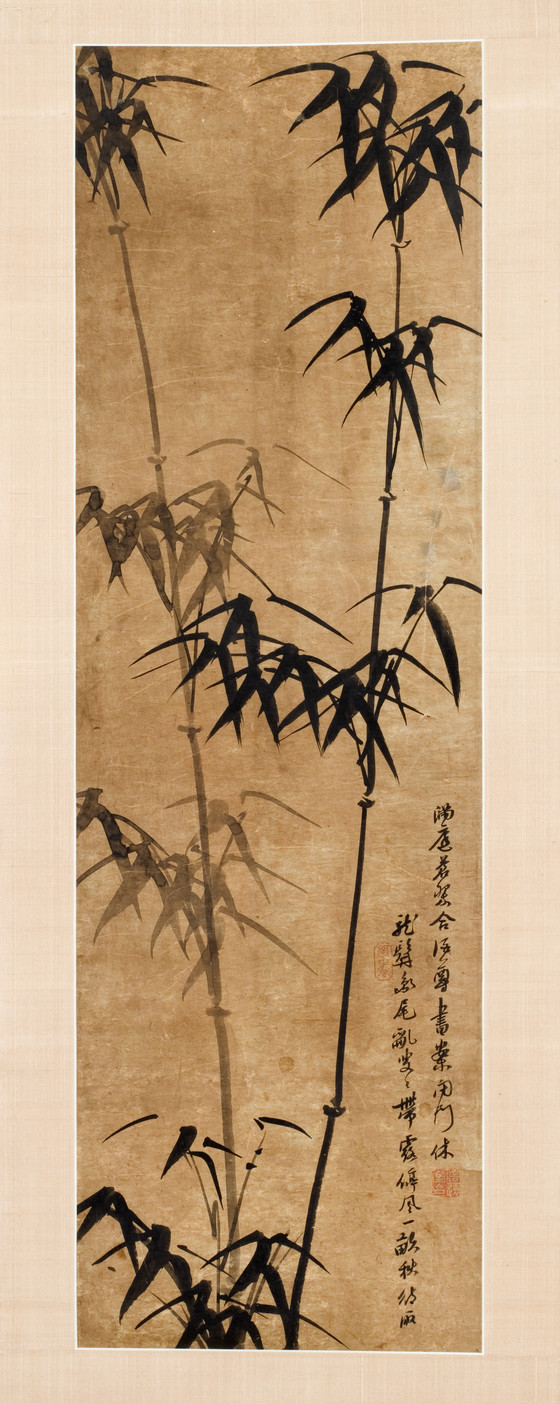

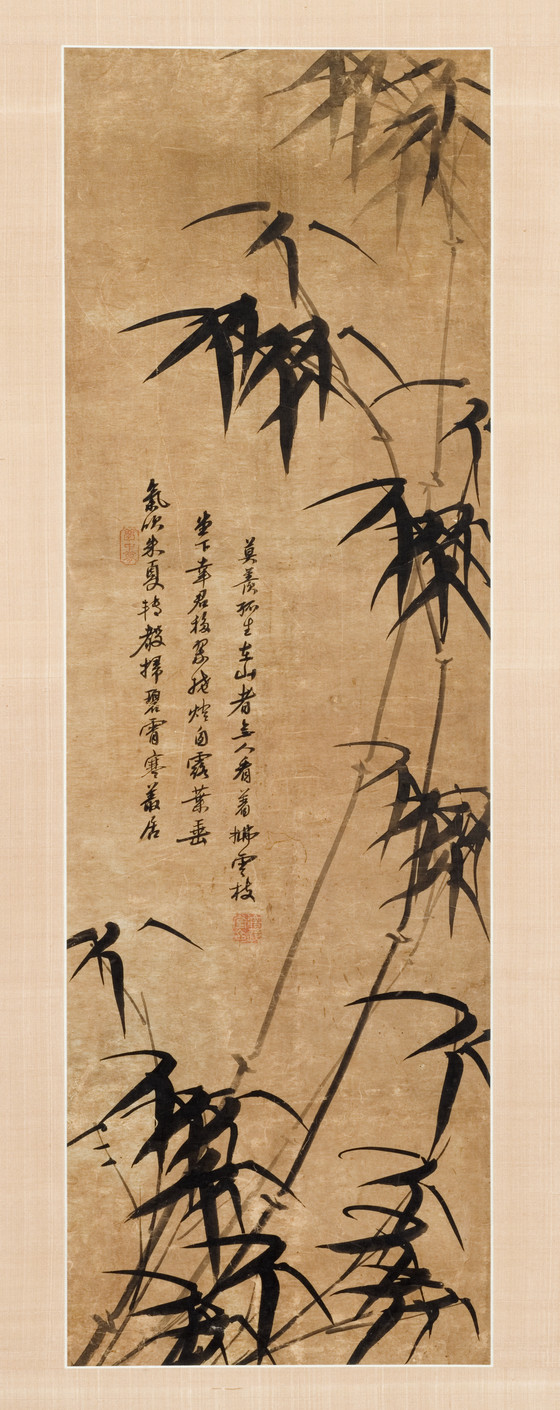

Around the seventeenth century, during the middle Joseon period, several Korean painting masters specialized in bamboo. For example, Yi Jeong (1554-1622 fully mastered the Chinese Ming dynasty techniques and methods of painting bamboo while also creating his own style. His bamboo paintings are known for their powerful and tense expression, a result of his quick brushstrokes and simple, symbolic compositions (fig. 1). Followers of Yi Jeong who also focused on bamboo include Yi Jing (born 1581), Heo Mok (1595-1682), and Kim Se Lok (1601-1689).

The bamboo paintings of Yu Deokjang (1675-1756) are representative of this genre in the late Joseon period. In contrast to the emphasis on symbolism by the earlier master Yi Jeong, Yu depicted bamboo with great realism. Other elements, such as rocks, are rendered smoothly and delicately, and the overall painting by Yu is calm and atmospheric (fig. 2). The influential art critic, artist, and patron Gang Sehwang (1712-1791) also often painted bamboo, which suggests a continued interest in the subject among literati in the eighteenth century. During the nineteenth century, a literati painter who often depicted bamboo was Shin Wui (1769-1845). Applying heavy, moist ink washes, he was less interested in symbolism than in exploring the pictorial effects of the subject (fig. 3).

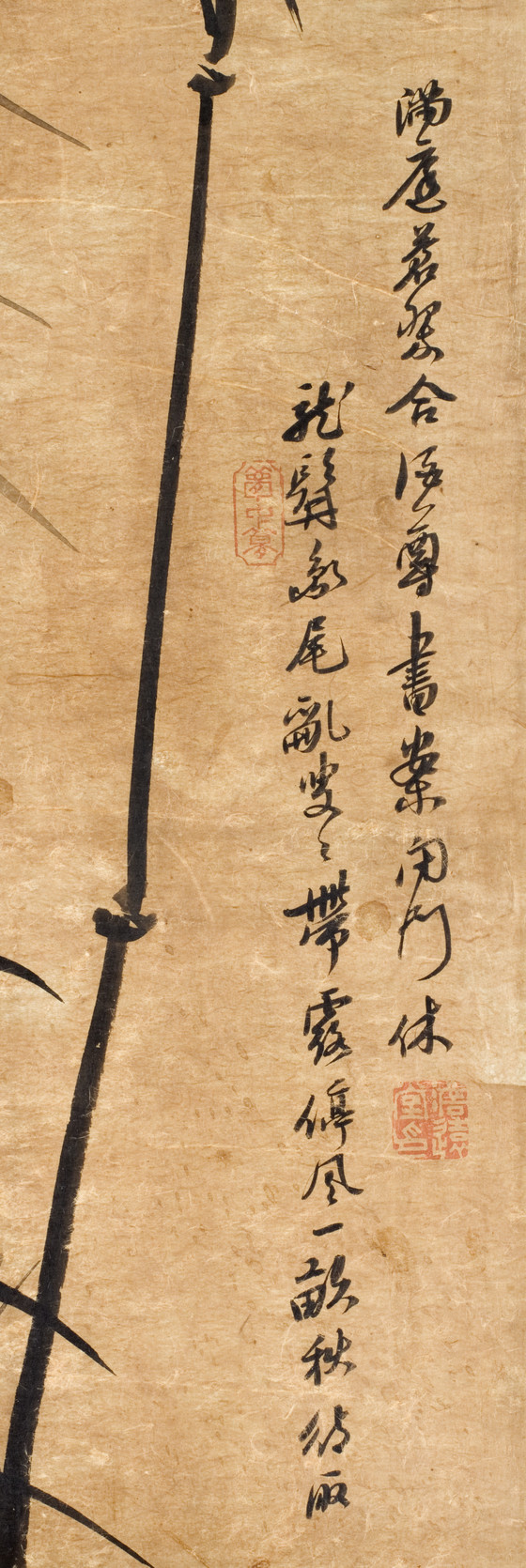

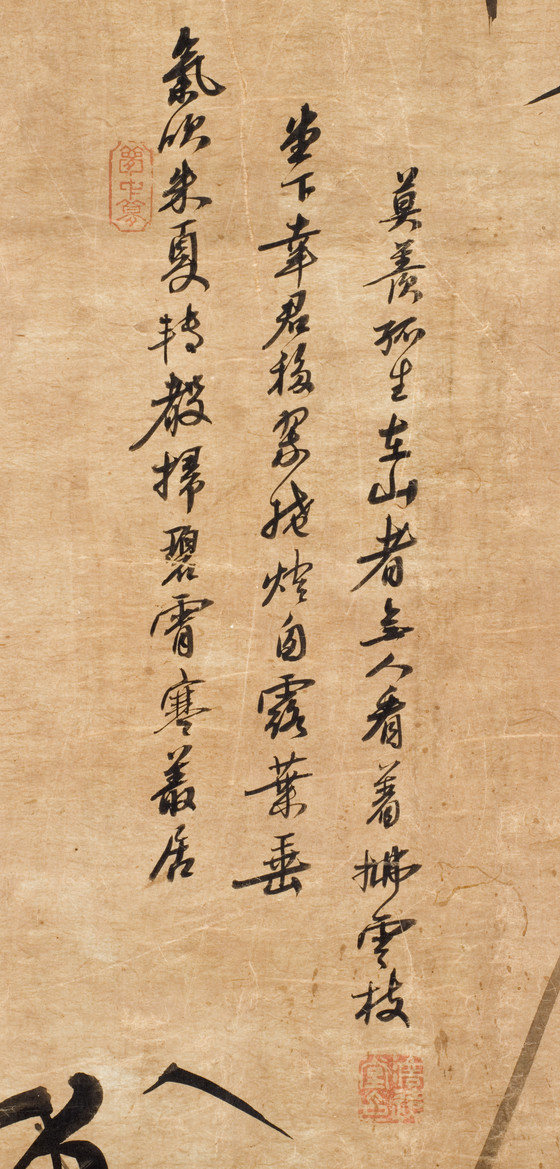

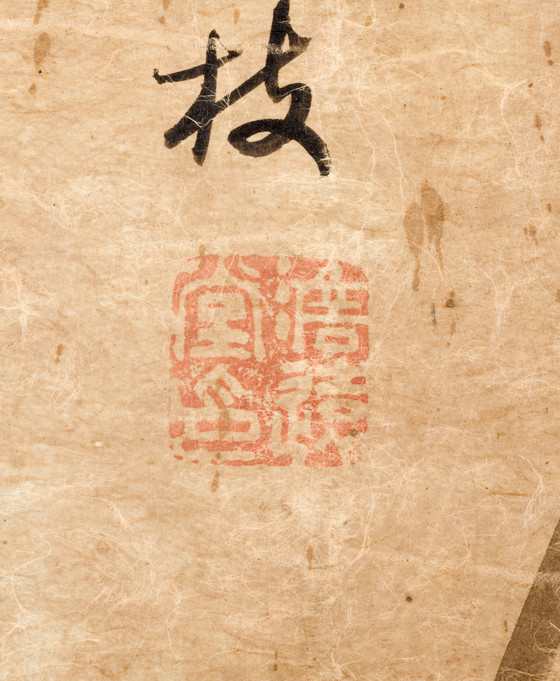

LACMA’s two bamboo paintings were probably a pair executed in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century. In each composition, two bamboo stalks are juxtaposed and painted with subtly varying ink tones to increase the sense of depth and resonance. Each bears a seal reading “Seal of Damwondang” impressed at the end of a two-line poem about bamboo, which might suggest an early-twentieth-century date (det. 1). The only artist identified with the Damwondang pen name is Jo Giseok (1897-1935), a regional painter of bamboo and orchids who practiced in Jolla province. Additional seals reading “Mongjoongmong” (literally “dream in a dream”) appear to belong to a collector or friend of the artist, perhaps Yu Yeongwan (1892-1953), who was also a well-known local calligrapher and bamboo painter during the period of colonization between 1910 and 1945 (det. 2,3). Both Jo Giseok and Yu Yeongwan created works in the regional taste of Jolla province, an area historically known for producing many artists with a distinctive local style.

Footnotes

[1] Bak Insan, “Bamboo and Orchid Paintings in the Joseon Dynasty [Joseon wangjo nanjukhwa],” Gansong Munhwa 69 (Seoul: Hanguk minjok misul yeonguso, 2005), 105.

More...