Curator Notes

Henry Inman’s portrait of No-Tin illuminates the integral place of American Indians in the nation’s history and art history. Painted after a lost original by Charles Bird King, Inman’s portrait of No-Tin is an early and defining example of American artists’ efforts, pre-photography, to depict Native Americans for national posterity. The portrait is also a testament to a critical moment in the history of Native Americans.

Because Inman’s portrait survives, we know that No-Tin, which means Wind, was a Chippewa chief who came with his tribe’s delegation to Washington DC in the mid-1820s. Nothing is known of No-Tin’s own experiences during that visit, but he was one of scores of tribal leaders invited to the capitol by the U.S. government for negotiations, tours, and an audience with the President. The Chiefs would stay for several weeks, even months, for meetings and to experience Anglo American culture, all part of a federal diplomatic effort to pave the way for Indian removal and westward expansion.

This mission was cultivated most influentially by Thomas L. McKenney, head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, a division of the U.S. Department of War. McKenney had also made it his mission to collect and preserve Native American materials for a national collection. But it was the Indian delegations that inspired McKenney to add portraits to his collection and create a national Indian Gallery. In 1822, he commissioned King, a Washington DC portraitist, to capture their faces. The project was an attempt to produce visual documents that might represent and preserve the power he knew these Chiefs would soon lose.

The Chippewa, a corruption of the tribe name Ojibwa, were one of the largest and most powerful tribes in the Great Lakes territory and had extensive influence in the European fur trade. They controlled ore-rich, forested lands which they were largely able to protect—until 1837. In fact, No-Tin has been cited for his attempt to improve the conditions at Fort Snelling, in what is now Minnesota, where the Chippewa had to negotiate that 1837 treaty. No-Tin implored that the federal agents to provide better food rations, specifically more beef, for the tribe as they prepared to negotiate the inevitable cession of their lands: "You have everything around you, and can give us some of the cattle that are around us on the prairie."

King’s picture of No-Tin and over 130 other Indian Chiefs were all on permanent display to the public in the War Department offices, a major feature of all travel accounts and guides to the capitol. The passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830 further encouraged McKenney to make the portraits in the Indian Gallery as widely available to the public as possible. He knew that only a successful artist, one more accomplished and ambitious than King, could produce the kind of compelling paintings that would become well known outside Washington. That artist was Henry Inman.

Inman is among the best American artists of the early-nineteenth century. He established his studio in New York in 1824, quickly building his reputation as one of the most sought-after portraitists of his day, at a time when portraiture dominated artistic activity. Inman regularly received coveted commissions from the government and from the nation’s leading families. The Inman versions of the Indian portraits are original works of art in their own right. Such paintings reference a long and proud art historical tradition of copying masterpieces, as well as give us a unique perspective on lost originals. King’s originals were small records of his sitters. Inman enlarged the size of his canvases to make an artistic statement. Inman’s decision to increase the scale not only enhanced the significance of his paintings but also of each Chief. His large portraits deliberately put the Indian sitters on par with his renowned paintings of other prominent Americans. Inman’s portraits attained even greater significance after King’s portraits were transferred to the Smithsonian Institution’s art gallery, which burned in 1865, destroying all of King’s originals, including No-Tin.

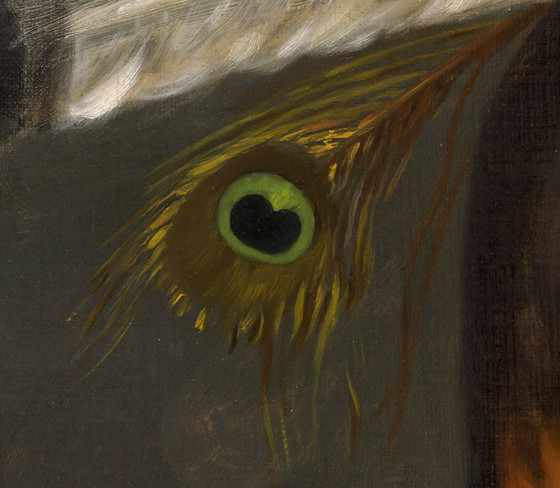

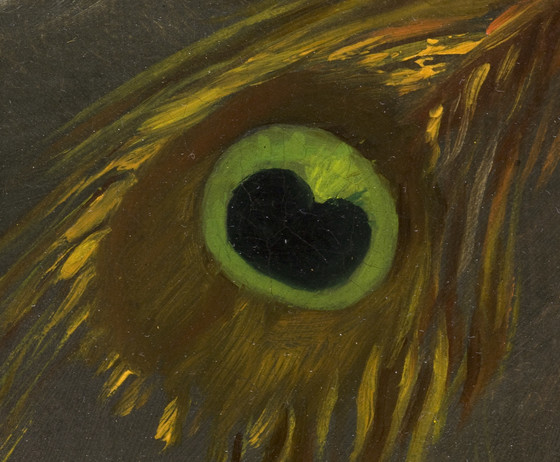

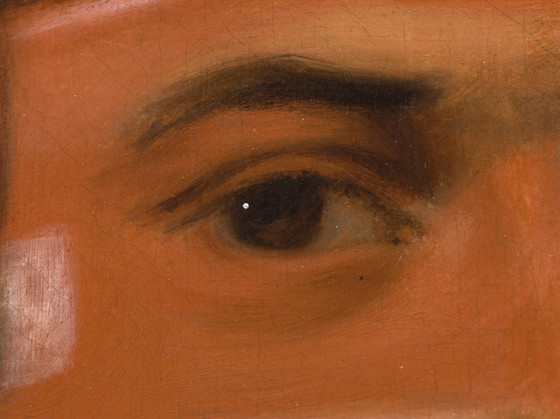

Inman’s portrait of No-Tin is in its original frame, and Inman beautifully painted No-Tin’s Chippewa costume details, such as the pink ostrich plume, the customized eagle feather, bead choker and orange and white face paint, decorations that would have been worn for special occasions—especially a diplomatic visit, or a portrait sitting, in Washington. No-Tin is wrapped elegantly in a green, possibly felt, blanket, the likes of which were commonly traded. His character is conveyed especially through his direct and steady gaze.

Inman’s art has prevented No-Tin from being lost to history. This rare portrait represents the inextricable place of American Indians in our national story, an essential perspective previously missing from LACMA’s presentation of American art. Now LACMA comprehensively represents the diverse faces of early America.

Austen Bailly, Assistant Curator, American Art, (2008)

More...