Curator Notes

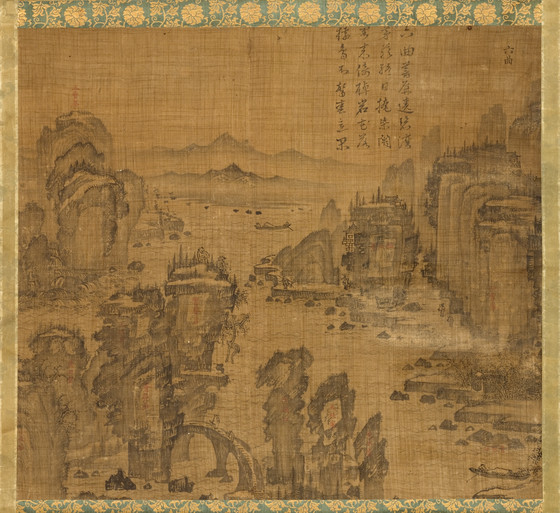

The Sixth Bend

In the Sixth bend, Canping Rock surrounds the jade-blue bay.

The brushwood door of the thatched-roof cottage is closed all day.

Guests come by rowboat, while flowers fall on the hills.

Monkeys and birds, enjoying the leisure of spring, are not startled.[1]

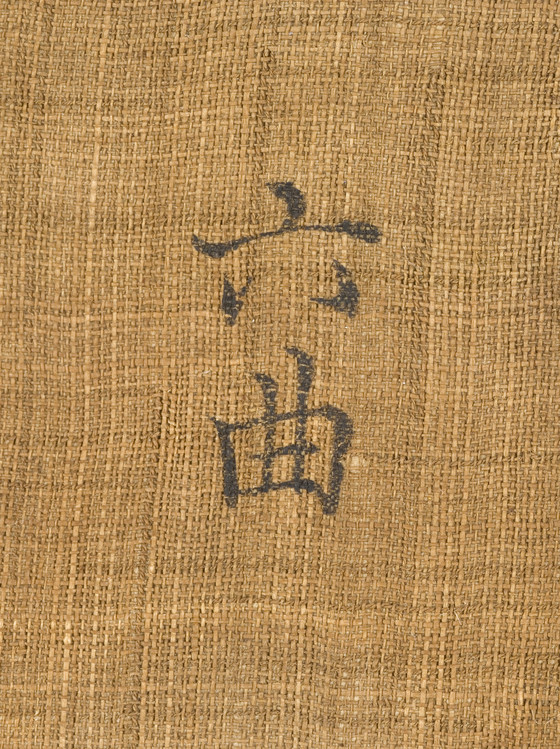

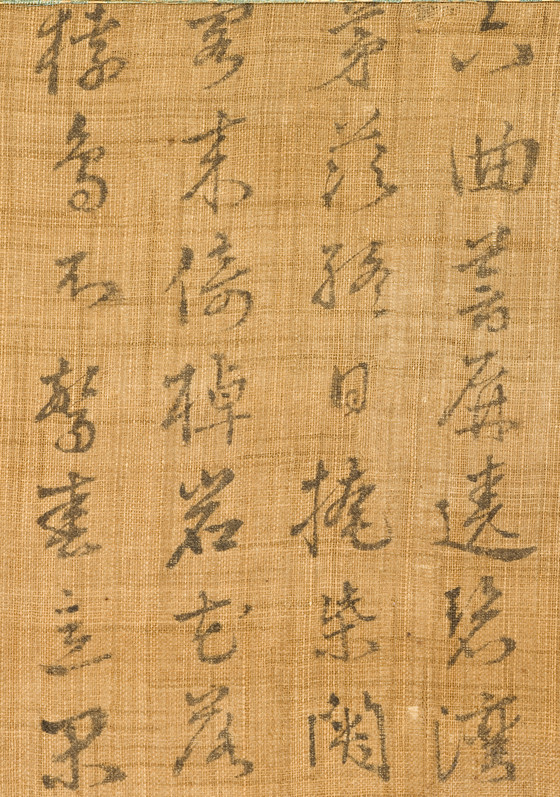

The inscription is by the Chinese philosopher Zhu Xi (1130-1200), from his poem “The Nine Bends of Mount Wuyi” in which he praises nine beautiful areas of this mountain in southern China’s Fujian province (det. 1). Zhu Xi, who is recognized as the founder of Neo-Confucian philosophy, spent more than fifty years lecturing and researching at his private estate, which was situated in this isolated area, far from the center of scholarly activity of the Yangzi delta area. In this ten-stanza poem, Zhu Xi illustrates views of Mount Wuyi, a place very significant to him personally and also to his philosophy. In the first stanza, he describes his estate, and in the following nine stanzas he portrays different bends along the river that he chose for their uniqueness and beauty.

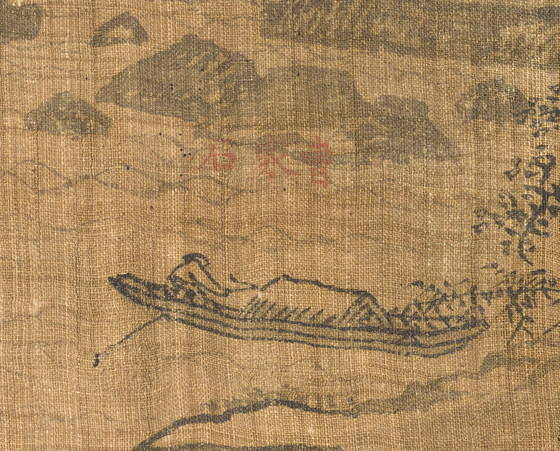

The painting is an illustration of the poem. Canping Rock, mentioned in the first line, is the craggy, layered rock with the connected bridge in the foreground (det. 2). A thatched-roof cottage can be seen on the lower riverbank at bottom right; although, according to the poem, its door is closed all day, in the painting it is open, welcoming guests. Visitors can be seen on two boats (det. 3) and on the bridge leading to Canping Rock, while monkeys are playing undisturbed on the cliffs (det. 1). The accuracy of the image as it relates to the description in the poem is reinforced by the identifications, in red ink, of the specific topographical features.

Foreign Artwork Record

A similar version of The Sixth of the Nine Bends at Mount Wuyi, China, dated 1592, was painted by the scholar artist Yi Seonggil (born 1562), who traveled to Ming dynasty China twice as a court envoy (fig. 1). Both paintings have very similar brushstrokes, shading, and mountain forms. Another painting of the subject includes a 1564 inscription by the famous Korean philosopher Yi Hwang (1501-1570) in the colophon at the end of the handscroll (fig. 2). Although stylistically similar, the mountain and rocks in LACMA’s version seem more formulaic, suggesting it is a slightly later work. Consequently, LACMA’s painting can safely be dated to the latter part of the seventeenth century.

In the colophon of the comparative painting and also in an essay, Yi Hwang wrote that there were numerous paintings of the Nine Bends of Mount Wuyi in circulation at that time. According to Yi, he personally commissioned several artists to paint the subject and provided them with models from which to copy, although he admitted he was not satisfied with many of them.[2] Why were Korean scholars so interested in images of the Nine Bends of Mount Wuyi during the early Joseon dynasty, when the subject was not very popular in China? In the sixteenth century, Neo-Confucian doctrines prevailed in Korea, and accordingly, Zhu Xi was highly esteemed by leading scholars of the day such as Yi Hwang and his pupil, Yi Yi (1536-1584). Zhu Xi’s philosophical and literary writings were imported to Korea, and his ideas – including his approach to nature – were adapted by his Korean followers.

One result of this respectful emulation of Zhu Xi by Korean scholars was their interest in dwelling amidst extraordinary natural surroundings to cultivate philosophical ideas. Yi Yi, for example, retired to Haeju Seokdam and composed a poem, “Nine Bends of Gosan,” about the region, following the rhyme scheme of Zhu Xi’s “Nine Bends of Mount Wuyi.” Other poems such as “The Nine Bends of Wunmun” by Bak Hadam (1479-1560) and “The Nine Bends of Muheul” by Jeong Gu (1543-1620) further illustrate how Korean scholars adapted Zhu Xi’s concept of the Nine Bends to indigenous Korean subjects. During the seventeenth century, the Noron school, a political faction, respected and stubbornly adhered to Zhu Xi’s philosophy. It was this group that created many of the known poems and paintings about Mount Wuyi and various other adaptations of the “Nine Bends.” Song Siyeol (1607-1689), a defender of the Noron school who was dedicated to preserving Zhu Xi’s philosophy, is known to have proposed a project to create a painting and poem album of the Nine Bends of Gosan. According to Song’s writings, he planned to invite nine scholars, each of whom would write a stanza about one bend. In selecting the poets, of course, Song only invited scholars of the Noron school.[3] Within this political and philosophical climate, the popularity of the subject of the Nine Bends of Mount Wuyi flourished during the seventeenth century and paintings continued to be produced until the nineteenth century. The LACMA painting can be understood in this context as a symbol of the Neo-Confucian scholar’s desire to live an ideal life of seclusion and rigorous self-cultivation.

Footnotes

[1] Translation modified from Jiyeon Kim, “Sacred Site: Paintings of Zhu Xi’s Retreat in Choson Dynasty Painting” (graduate seminar paper, History of Art, University of Southern California at Los Angeles), TKTK. The complete poem can be found in Zhu Xi, Meiyanji, in Siku quanshu, juan 9, 9.

[2] Yi Hwang, Twegyejip, gwon 43.

[3] For a more detailed discussion on the political discourse surrounding the Nine Bends paintings, see Cho Kyuhee, “Joseon yuhakeu ‘dotong’ eusikgwa gugokdo,” Yeoksa wa gyeonggye (Seoul, 2006), 1-24.

Additional References

Miguk Pakmulgwan Sojang Hanguk Munwhajae (The Korean Relics in the United States). Seoul: Hangukkukjae Munhwa Hyo*phwoi (International Cultural Society of Korea), 1989, 184 See other artworks in this book

More...