A half-length portrait, this painting depicts an official by the last name of An wearing an official hat and robe....

A half-length portrait, this painting depicts an official by the last name of An wearing an official hat and robe. It is apparent from the crane motif in the rank badge[1] on his robe that An was a scholar-official at the court (det. 1). Typical of Korean portrait painting, this work expresses the personality and character of the distinguished An.

Traditional Korean portraits commonly emphasized the face with much detail while the body and robes were more simplified. Yi Jaegwan’s portrait follows this tradition, but it is noteworthy because the artist used shading techniques, especially in the face (det. 2). The new Western technique of shading was introduced to Korea through China during the early nineteenth century, primarily through the frequent travels of Korean envoys in China.[2]

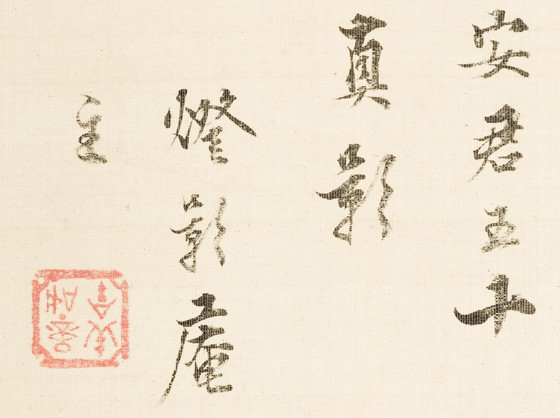

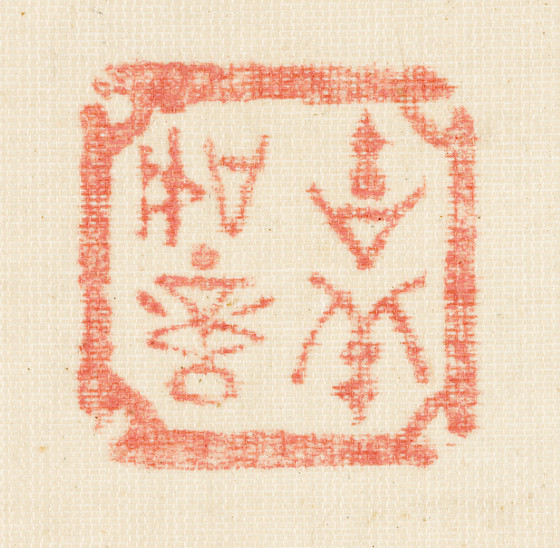

The author of the inscription on the top of the painting is Kim Jeonghui, the famous philosopher, scholar, art theorist, artist, and calligrapher.[3] Kim was the influential leader of a group of scholars and artists during the late Joseon period and he introduced to Korea the scholarship of epigraphy prevalent in China. The last line of the inscription, which reads “the owner of Light Shadow Hut [Deungyeongam],” indicates that the writer is Kim Jeonghui because Light Shadow Hut was the name of his study. In addition, the two seals reading “gilsang yeonyi” and “Samgodang,” identify Kim (det. 3).

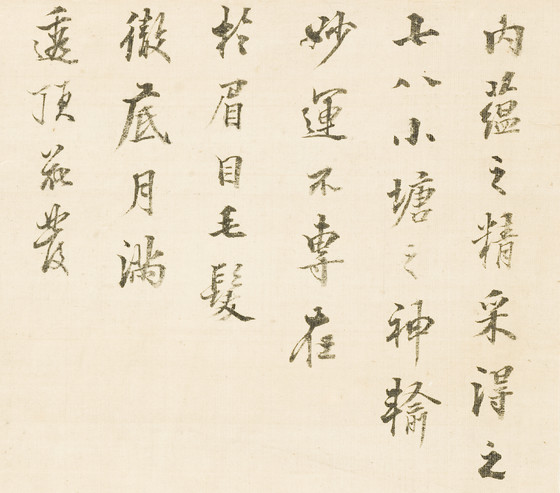

The first four lines of the inscription reflect on the portrait: “catching seven- or eight-tenths of the transcendental inner essence [of the sitter], Sodang’s marvelous skill executing the image lies not entirely on the eyebrows, eyes, and hair” (det. 4,5). In this passage, Kim Jeonghui praises Yi Jaegwan (whom he calls Sodang) for his success in capturing the spirit of the sitter.

Yi Jaegwan was a professional painter who received a higher rank in court after successfully copying the royal portrait of King Taejong, the first king of Joseon. Although he never received formal academic training as an artist, Yi was versatile in a variety of styles and subject matter including landscapes, figures, flowers and birds, fish, and portraits. Yi Jaegwan was skilled in conceptual literati ink styles of figure and landscape painting, but he could also create very detail-oriented and realistic paintings, seen here in the depiction of An’s belt hook (det. 1). Cho Hiryong (1789-1866), an artist and critic, admired Yi Jaegwan’s painting, noting that “in 100 years before and after, there is no such excellent painter.”[4] Yi’s paintings were popular in Japan, and many Japanese acquired his works while visiting Doraeguan in the Korean city of Busan.[5]

Image not found

Yi Jaegwan received the highest praise for his portraits, including from the master Kim Jeonghui. In 1827, Kim, a fastidious critic, recommended Yi from among his many students to create a new version of the portrait of Yi Hyonbo (1467-1555), an official and famous poet of the middle Joseon period.[6] Kim Jeonghui also inscribed another work by Yi Jaegwan that is similar to LACMA’s portrait, his portrait of Gang Yi’o (born 1788) (fig. 1). Yi Jaegwan, along with Yi Hancheol (born 1812), is recognized by contemporary and later scholars as a representative portrait painter of the nineteenth century.

Footnotes

[1] Military officials, for example, were identifiable by the tigers on their rank badges. LACMA’s collections include rank badges for the different official divisions; for examples, see Rank Badge (Hyungbae) with Two Tigers (M.2000.15.194), Rank Badge (Hyungbae) with Two Cranes amidst Clouds (M.2000.15.197a-b), and Rank Badge (Hyungbae) with Two Cranes amidst Clouds (M.2000.15.198).

[2] For more about the issues surrounding the introduction of Western painting techniques and styles to Korea, see Yi Sung-mi, Joseon sidae geurim sokeui seoyang hwabeop [Western Painting Techniques in Joseon Paintings] (Seoul: Daewonsa, 2000).

[3] The National Museum of Korea in Seoul recently held a special exhibition to commemorate the 150th anniversary of his death. See National Museum of Korea, Chusa Kim Jeonghui: Hakye ilchi eu gyeongji[Chusa Kim Jeonghui: The Harmonious State of Scholarship and Art] (Seoul: National Museum of Korea, 2006).

[4] 4. Cho Yu Jaeso and Cho Hiryong, Yihwang gyonmunluk, Hosan waesa (Seoul: Asaea munhwasa, 1974), 60-61.

[5] Yi Wonbok, Painting[Huihwa] (Seoul: Sol, 2005), 250.

[6] Park Eunsun, “Nongam Yi Hyonbo’s portrait and ‘Yeongjeong gaemo yilgi’,” Misulsahak yeongu 242, 243 (2004, 9), 225-54.

More...