Curator Notes

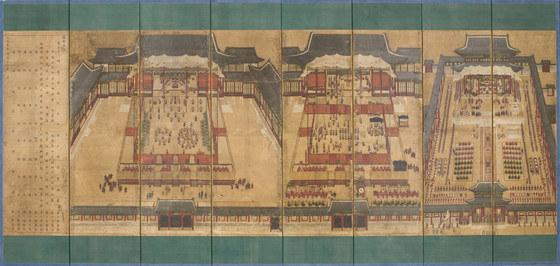

This colorful screen documents the royal banquet ceremonies held in celebration of the sixtieth birthday of Queen Mother Sinjeong (1808-1890).[1] Her life, marked by tragedy at times, was intertwined with the political turmoil and power struggles of the nineteenth-century Korean court. Lady Cho, as she was called before she became a member of the royal family, married a crown prince when she was only eleven years old but, sadly, her young husband died before ascending the throne. The dowager queen outlived her son, King Heonjong (reigned 1834-1849), who also died young. After failing to install a relative on the throne after her son’s death, Queen Mother Sinjeong allied with Yi Ha’eung (1820-1898), who was soon to be Daewongun,[2] and used her influence to name the Daewongun’s second son, from a distant royal family, as the next king. Twelve-year-old King Gojong reigned from 1864 to 1907 and, as his regent, the Daewongun governed the court for the next ten years, at a most crucial moment in Korean history.

The series of birthday celebrations depicted in Sixtieth Birthday Banquet for Dowager Queen Sinjeong in Gyeongbok Palace took place in 1868, in the early years of Gojong’s rule. The banquet ceremony for the Queen Mother was initiated and strongly supported by the Daewongun as regent. According to the Ceremonial Regulations for a Banquet (Jinchan uigye)[3] – the official record of the schedule of events, locations, and officials in attendance, as well as the proper decoration, costumes, dances, and musical performances – the banquet began on the sixth day of the twelfth month in Geunjeong Hall of Gyeongbok Palace and lasted several days. It was the first major event to take place in the newly reconstructed Gyeongbok Palace, which had been completed one year before under the direction of the Daewongun.

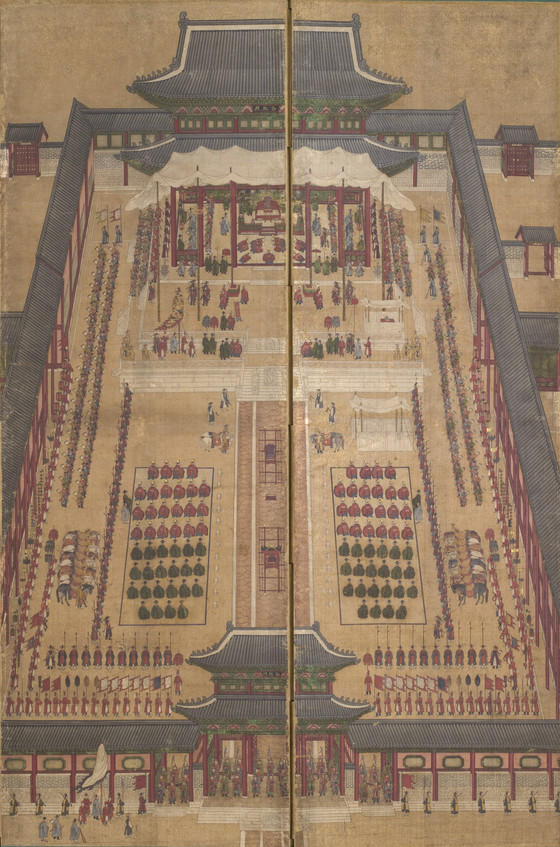

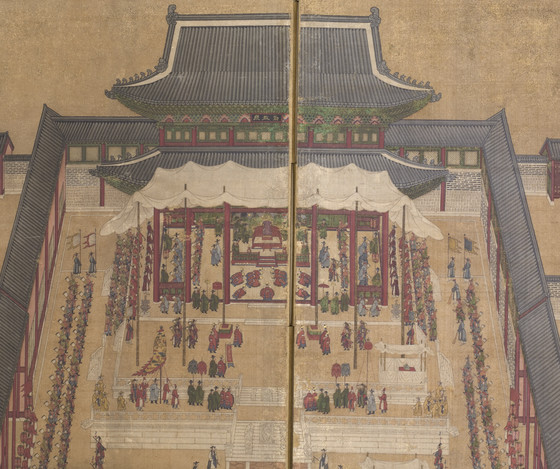

The first scene, on the two right panels, depicts the Great Court Ceremony at the beginning of the celebration, in Throne Hall (Geonjeongjeon) (det. 1). This, the most formal ritual of the event, was staged in the king’s hall with precise and orderly processions of officers and several royal palanquins. In the center of the scene, an official recites Queen Mother Sinjeong’s accomplishments and receives the king’s declaration to commence the celebration (det. 2). Typical of royal documentary painting, the king’s presence is symbolized by the empty throne in front of the Sun, Moon and Five Peaks screen.

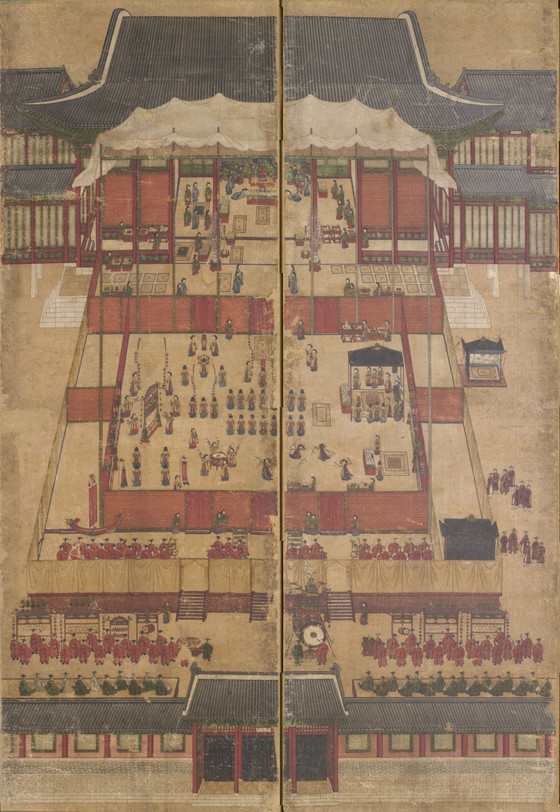

The second scene, on the third and fourth panels from the right, records the more private celebration that took place on the same day in the inner quarters at Gangryeongjeon (det. 3). This event was organized by King Gojong, his queen, and the Daewongun and his wife, among others, and many noble men and women were invited. It is interesting to note that the female and male participants were assembled into separate spaces for different rituals: the women sit near Queen Mother Sinjeong in the main hall in a formal ceremony, while the men, including the king, watch the dance and musical performances in the lower courtyard (det. 4).

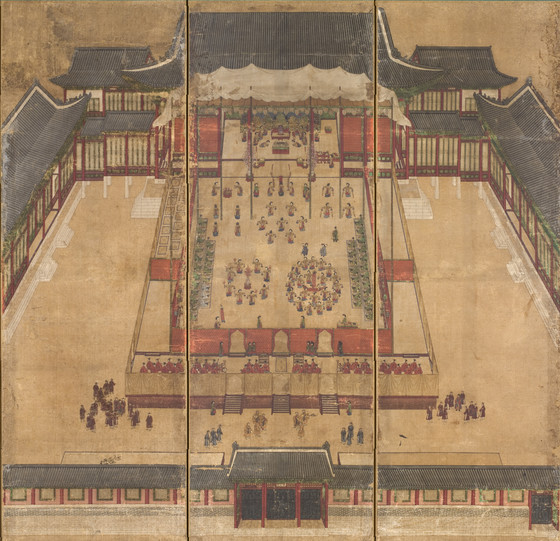

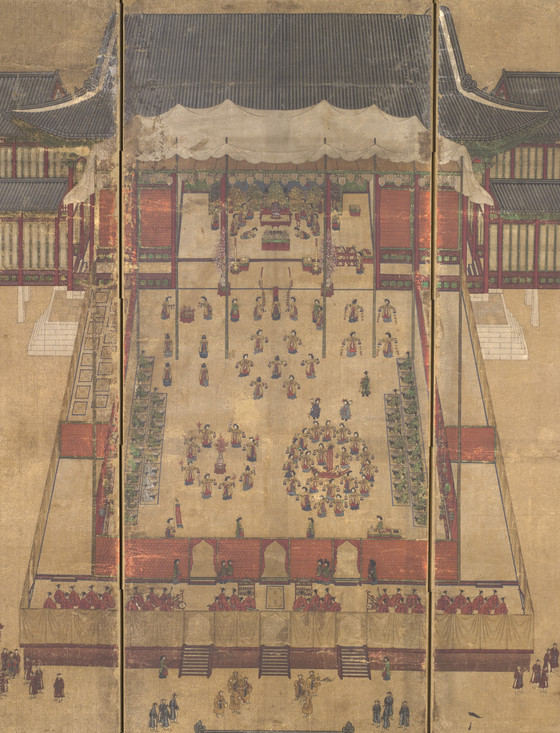

The next day, another large celebration took place at Gangryeongjeon to show appreciation to all the participants for their service (det. 5). The third scene on the screen illustrates this final banquet, which lasted into the night, as indicated by the two large candles and the lamps hung under the roof of the hall (det. 6). This scene is larger than the previous two scenes, occupying three panels, and it records in great detail the architecture and ceremonial performances, including five specific dances (det. 7). Here, the red screens separating the male and female participants have been removed, suggesting that the guests were relaxing and enjoying the banquet.

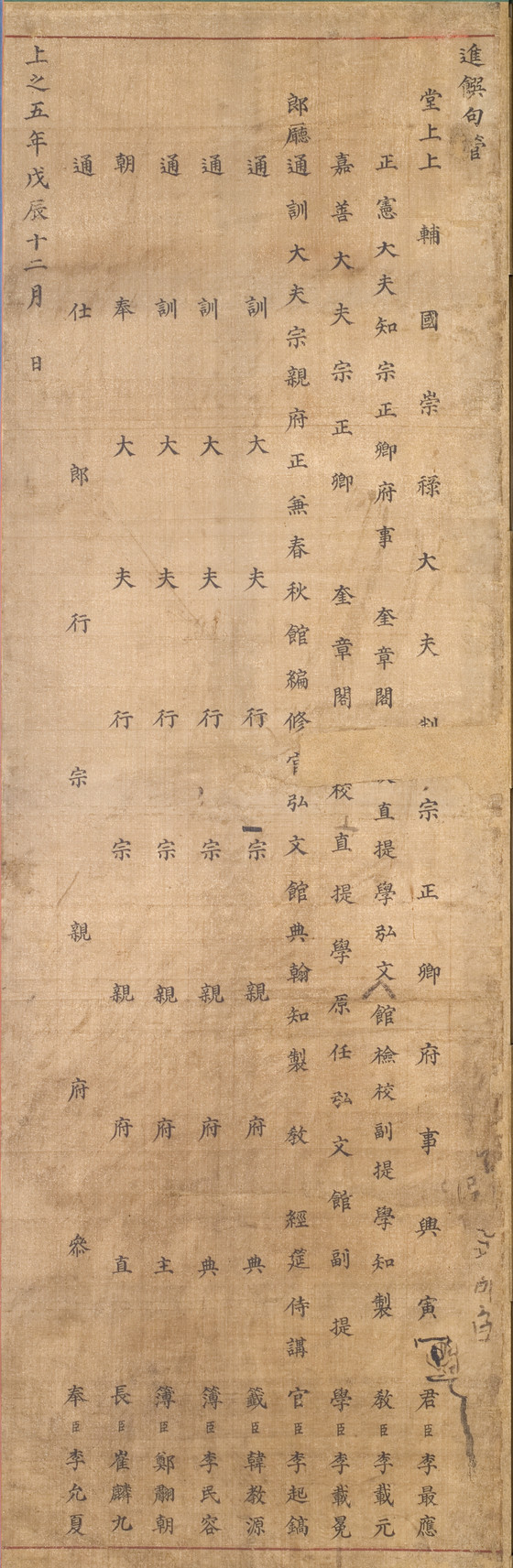

A final panel on the left records the names of the main officials who organized and supervised the celebrations (det. 8). The list of officials, mostly relatives of King Gojong and the Daewongun, includes, for example, Yi Choi’eung (1815-1882), the Daewongun’s elder son; Yi Jaewon (1831-1891), the eldest cousin of King Gojong; and Yi Jaemyon (1845-1912), the Daewongun’s first son and King Gojong’s older brother. According to the Ceremonial Regulations for a Banquet (Jinchan uigye), because the banquet was planned as a private family event rather than as a national public spectacle, the event could be organized by a group chosen by the royal family, rather than by the official event planning bureau.

Seven versions of this screen were painted in 1869 to save in several palace buildings, at the very expensive cost of almost 1085 nyang. Although no artist names are inscribed on LACMA’s screen, records indicate that ten artists including Lim Jaesoon, Yoo Sook, and Yi Hancheol (born 1812) were involved, because they are mentioned in the Ceremonial Regulations for a Banquet (Jinchan uigye) as prize recipients.[4]

By the end of the eighteenth century, Korean royal banquet paintings had become codified and were mostly executed in a screen format with eight or ten panels. Because of the documentary nature of the screens, the artists faithfully followed the official Ceremonial Regulations (Uigwe), volumes which included woodblock print illustrations indicating exact details of the architecture and the arrangement of the event. Consequently, by the nineteenth century, artists had all but eliminated the landscape scenes of earlier banquet paintings. Painted with great detail, LACMA’s screen is a valuable asset for understanding documentary painting and the political atmosphere of Korea in the early nineteenth century.

Footnotes

[1] For a more detailed discussion of this painting, see Burglind Jungmann, “Documentary Record Versus Decorative Representation: a Queen’s Birthday Celebration at the Korea Court,” Arts Asiatique, vol. 62, 2007.

[2] Daewongun was an official title given to the father of a boy who had ascended the throne but who was not the son of the preceding king. During the Joseon dynasty, there were only three Daewongun and, of those three, Yi Ha’eung was the most well known.

[3] The book is now in Gyujanggak Library at Seoul National University. Library Call No. 14374.

[4] Ceremonial Regulations for a Banquet (Jinchan uigye), gwon 2, 43.

Additional References

Miguk Pakmulgwan Sojang Hanguk Munwhajae (The Korean Relics in the United States). Seoul: Hangukkukjae Munhwa Hyo*phwoi (International Cultural Society of Korea), 1989, 198, 163, Possible error by publisher See other artworks in this book

Miguk Pakmulgwan Sojang Hanguk Munwhajae (The Korean Relics in the United States). Seoul: Hangukkukjae Munhwa Hyo*phwoi (International Cultural Society of Korea), 1989, 198, 163, Possible error by publisher See other artworks in this book

More...

Bibliography

- Han, Hyongjeong Kim. 2013. In Grand Style: Celebrations in Korean Art During the Joseon Dynasty. San Francisco: Asian Art Museum.

- Queens and Concubines of the Joseon Dynasty. Seoul: National Palace Museum of Korea, 2015.

- Miguk Pakmulgwan Sojang Hanguk Munwhajae (The Korean Relics in the United States). Seoul: Hangukkukjae Munhwa Hyo*phwoi (International Cultural Society of Korea), 1989.

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art. New York: Thames and Hudson, 2003.

- Korean Art Collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, U.S.A. Daejeon, Republic of Korea: National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage, 2012.

- Coleman, Patrick, ed. The Art of Music. San Diego: San Diego Museum of Art, 2015.