Curator Notes

Bamboo, plum, orchid, and chrysanthemum are praised in the literature and arts of East Asia as the Four Gentlemen, four plants that represent the ideal virtues of a scholar-official.[1] Bamboo is perhaps the most highly revered for several reasons. Because bamboo can bend but does not break, it represents a scholar or official who never compromises his moral ethics. The bamboo plant grows straight and does not change color and is thus also a symbol of constant loyalty. Scholars often gave paintings of bamboo to their friends to show their loyalty and friendship or displayed such paintings in their quarters to remind themselves of their ideals and beliefs. The plant itself was also important because it was widely used for scholars’ objects such as brush handles, fans, and brush holders. During the Joseon period, the bamboo motif was depicted on ceramics, lacquer, and wooden stationery boxes for use in the scholar’s studio.

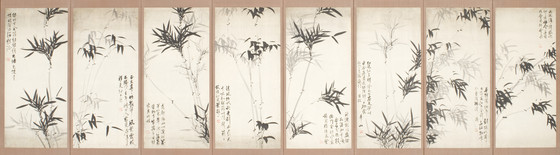

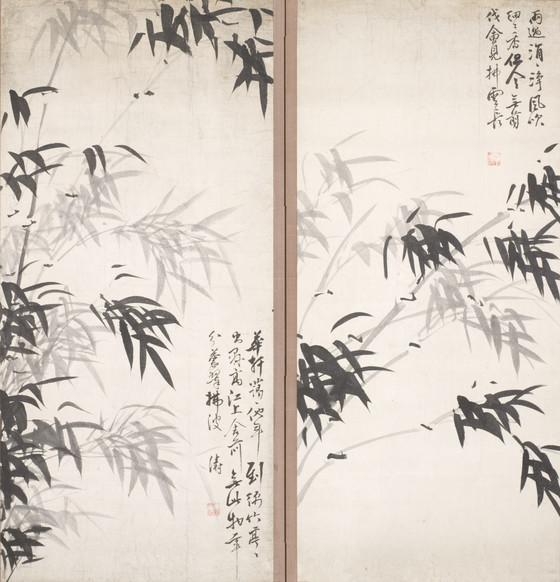

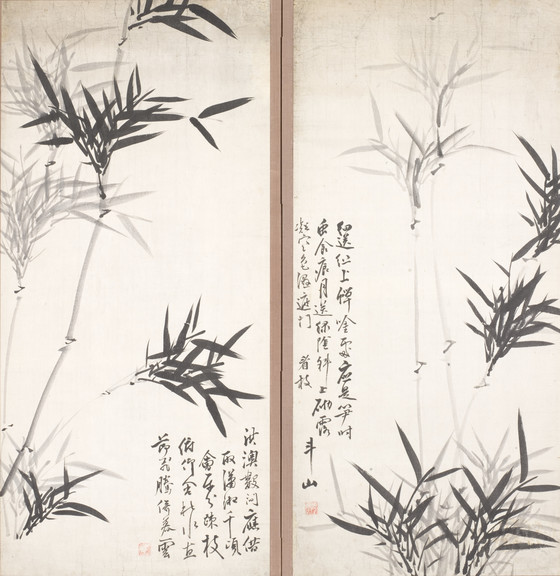

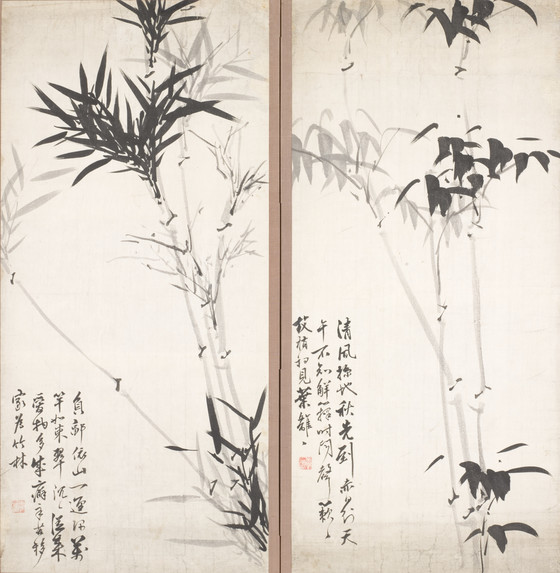

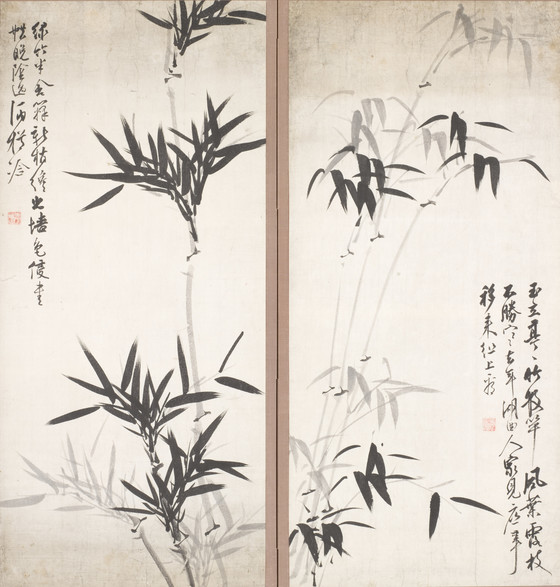

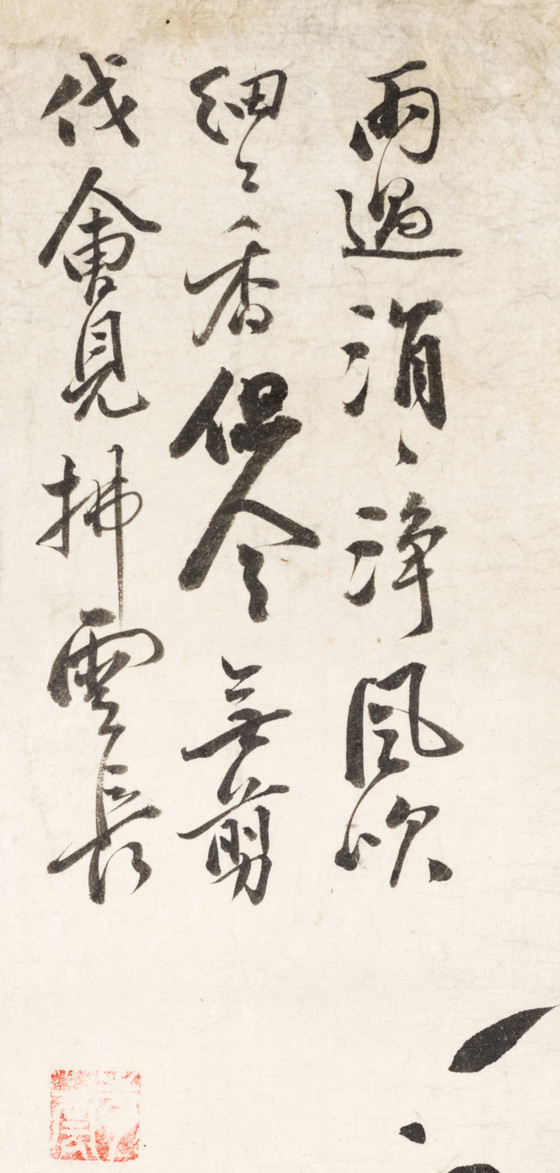

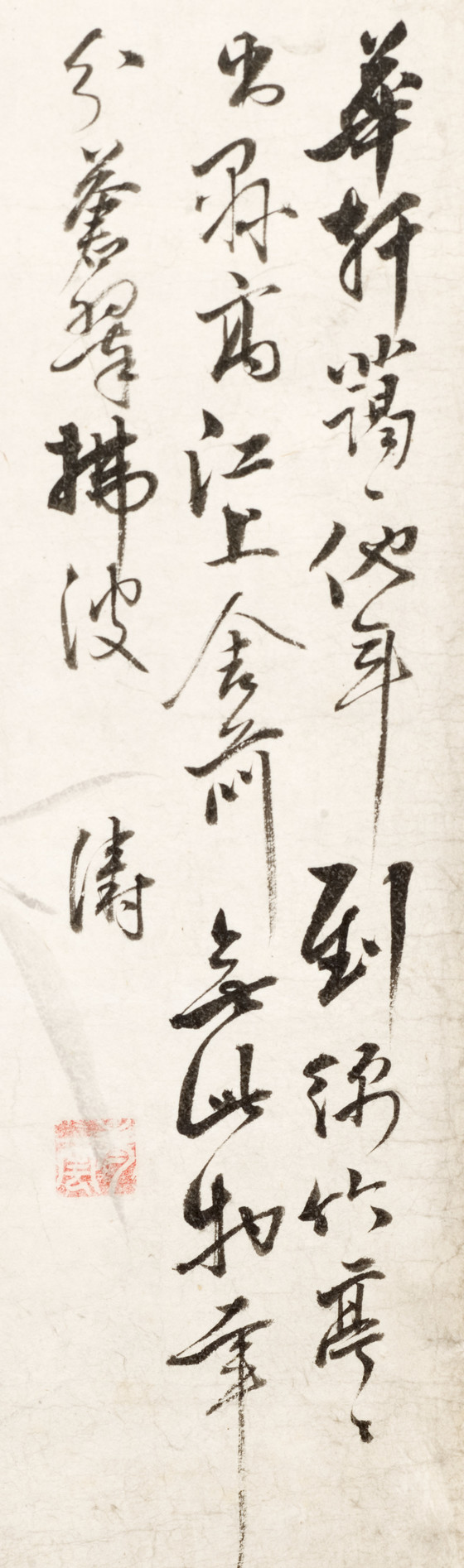

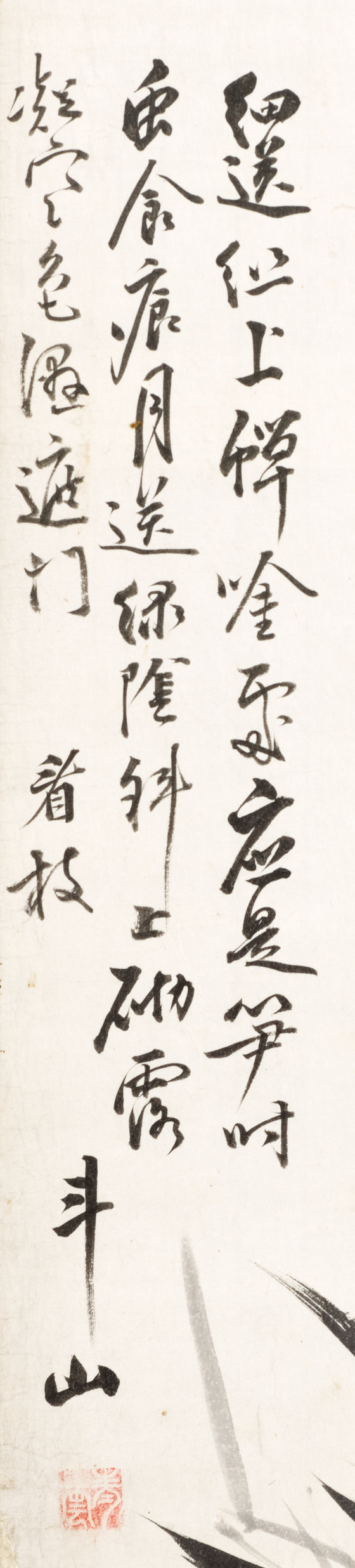

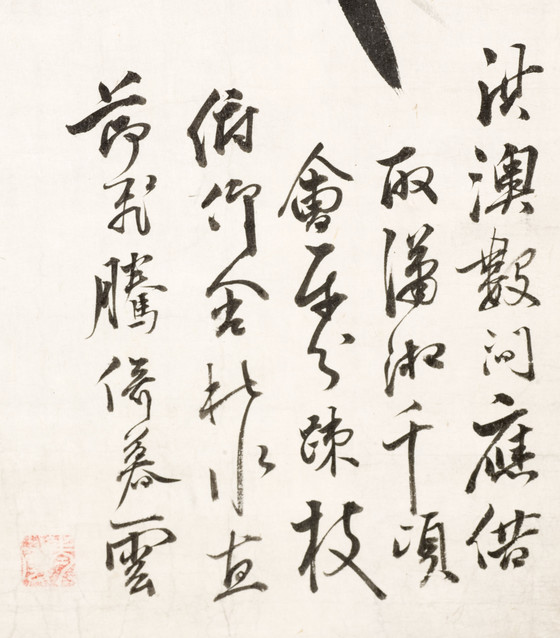

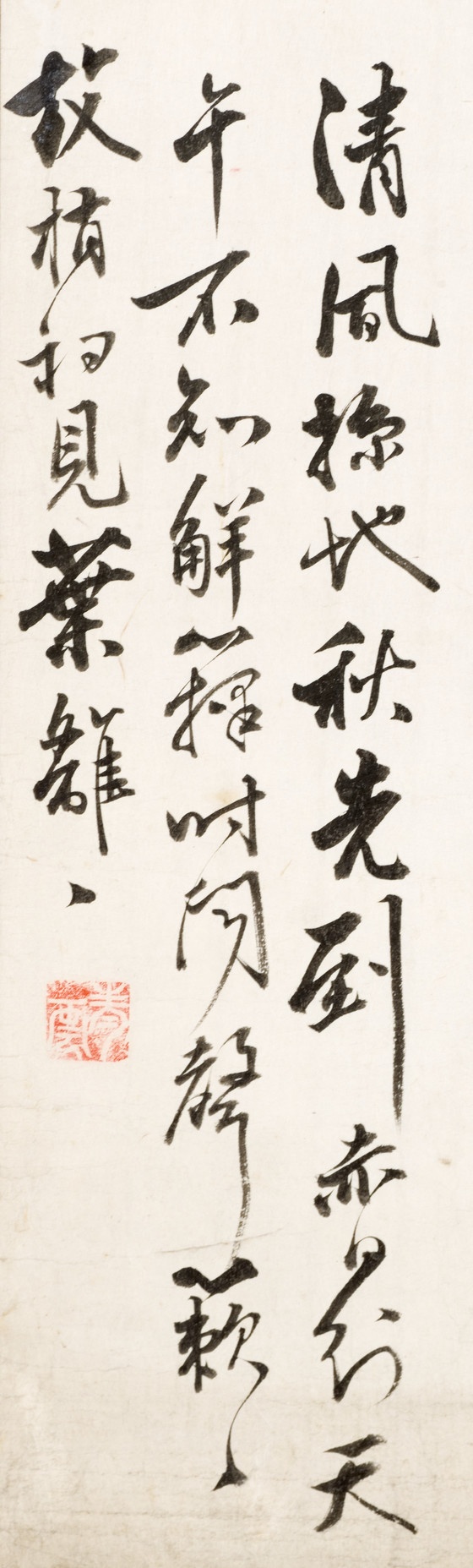

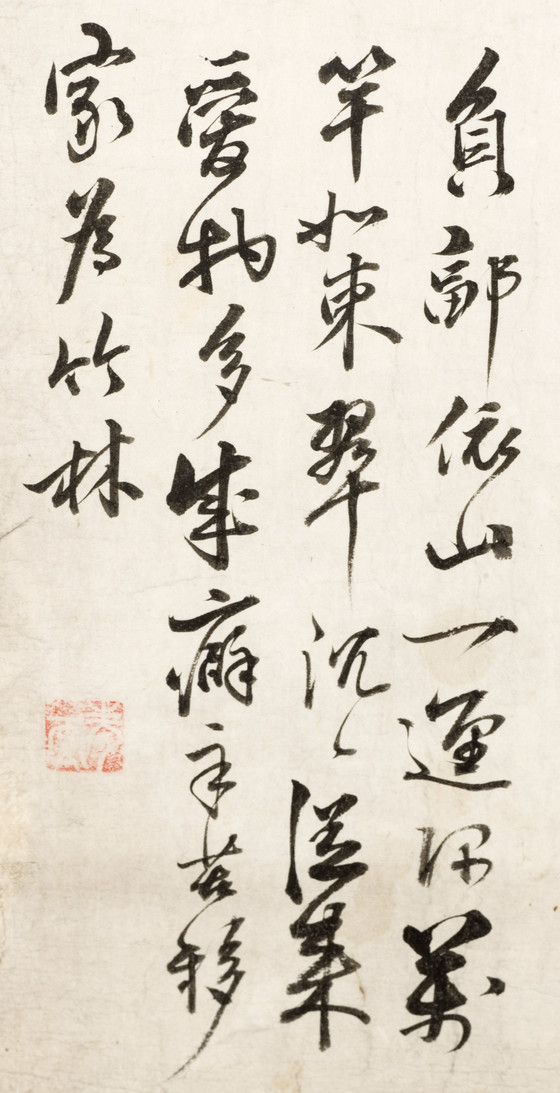

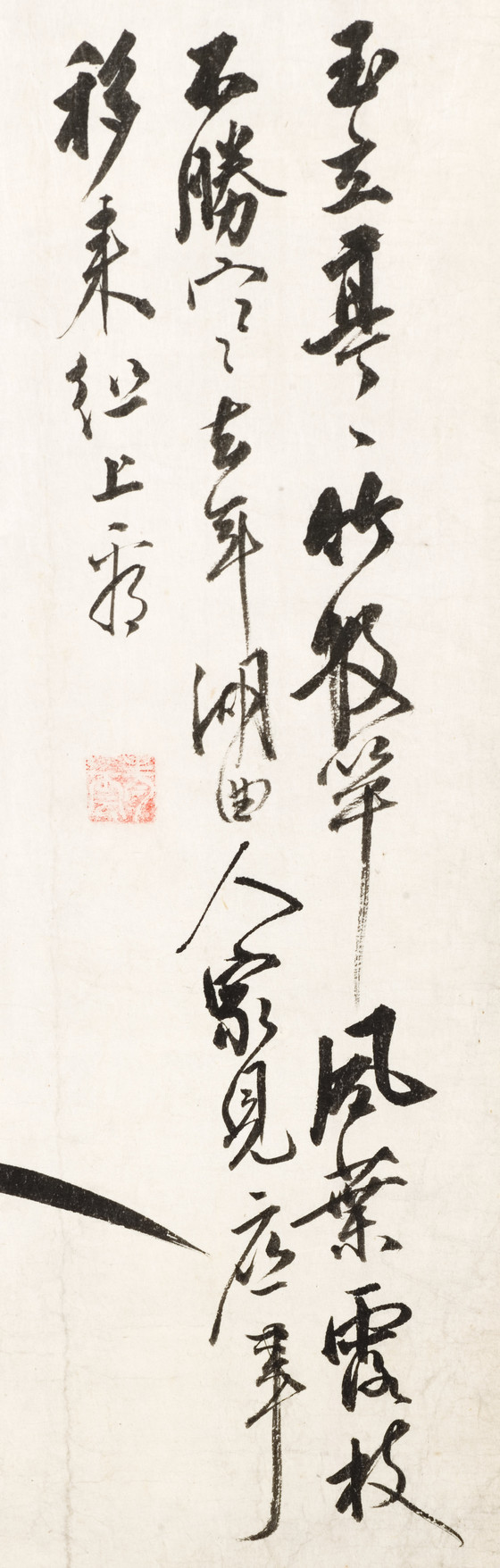

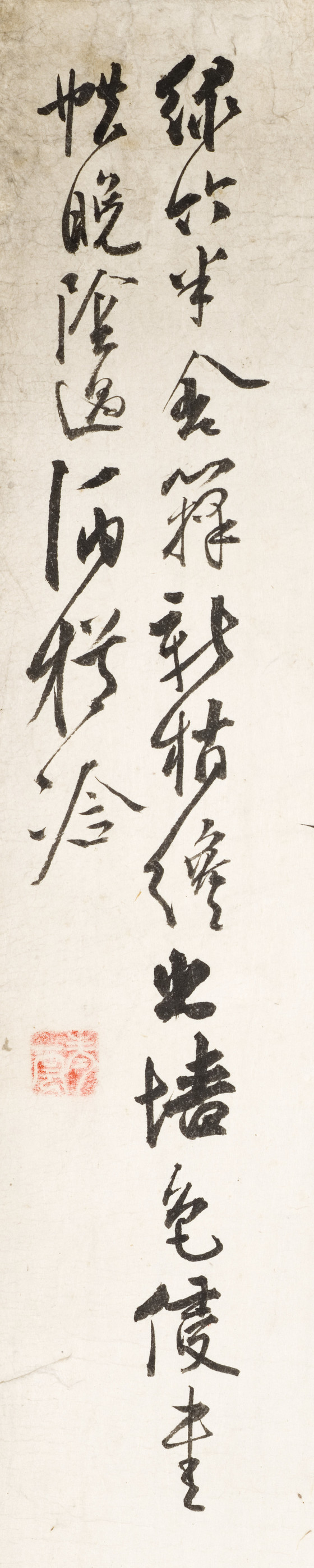

This eight-panel screen beautifully demonstrates the variety of forms that the bamboo plant can take. Each panel contains a five- or seven-character poem praising different aspects of bamboo and its ability to harmonize with nature. Painted in strongly contrasting tones of black ink, the strokes that form the connecting joints of the bamboo are distinctive with their dark tones and sharp angles.

Each poem is followed by the artist’s seal, which reads “Cheongwun” (det. 1). Cheongwun is the pen name of Gang Jinhui, who is probably more well known for being a government diplomat at the end of the nineteenth century. He accompanied the first Korean ambassador to the United States, Pak Jeongyang (1841-1904), on a trip across America in 1887 to deliver a letter from King Gojong to President Grover Cleveland in Washington, D.C. Gang is also recorded as the first Korean painter to illustrate the scenery of America. As a result of his experiences, he created at least one oil painting depicting two trains and a boat surrounded by Western-style buildings, which he titled Study of Fire Train.[2] When he returned from the United States, Gang became a high official in the Ministry of Justice. After retiring from government service in 1911, Gang became a professor for the Association of Painting and Calligraphy and devoted his time to teaching art. In 1919, he and twelve other artists founded another school of painting and calligraphy by the same name. A true scholar with many interests, Gang also wrote a book about his seal collection, which is now in the National Folk Museum in Korea. Gang Jinhui’s legacy today lies in his clerical script calligraphy and plum paintings.

The subject of bamboo became controversial among artists who were experiencing the rapid modernization of Korea in the very early years of the twentieth century. Some radical artists and art theorists, including Yi Hanbok and Ham Seokju, claimed in the 1920s that calligraphy and the tradition of the subject of the Four Gentlemen were left over from the feudal system and had no aesthetic value. Yi Hanbok even argued that the juried national art competition should exclude the subject. To counter these arguments, critics such as Shim Youngseob and Yi Taejun came out in support of calligraphy and traditional painting subjects. They argued that calligraphy and paintings of the Four Gentlemen exhibited the basic principles of Eastern and Western arts, the deep creativity of artist, and a very modern aesthetic.[3]

The most representative painters of bamboo by the beginning of the twentieth century were Kim Eungwon (1855-1921), Kim Gyujin (1868-1933), and a politician, Min Youngik (1860-1914). This screen is one of a very few of Gang Jinhui’s bamboo paintings that are extant, which makes it particularly important. Along with the pair of scroll paintings of bamboo in LACMA’s collection, this screen shows the continuity of the long tradition of bamboo painting. It offers a glimpse into the period in which it was produced and shows the artist’s role in the complex artistic and political context of the time. It is interesting to note that the letter that Gang Jinhui and the ambassador delivered to President Cleveland urged the United States to support Korea’s independence.

Footnotes

[1] For a brief explanation of the characteristics of each plant as well as a history of bamboo painting, refer to the essay in this online exhibition on the pair of bamboo hanging scrolls, M.2000.15.37-.38.

[2] The painting is now in the Gansong Art Museum in Seoul. Yi Guyeol, The Back Stories of Our Modern Art [Wuri gundae misul dyeutyiyagi](Seoul: Dolbaegye, 2005).

[3] For a more detailed discussion of the issue, see Choi Yeol, History of Korean Modern Art Criticism [Hanguk geundae misul pyongronsa] (Seoul: Yeolhwadang, 2001), 49–51.

More...