Curator Notes

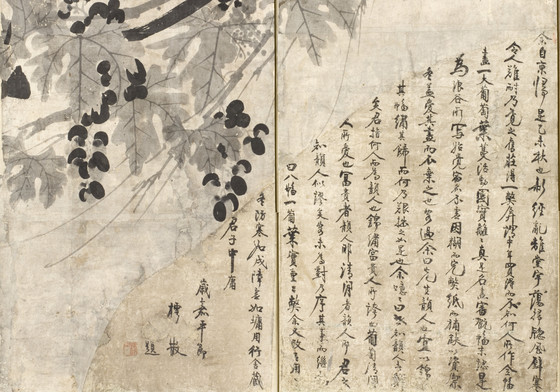

In this attractive painting, an immense, dynamic grapevine dances across the surface of the eight-panel screen. Grape leaves in various forms flutter in the wind while the grapes, painted in dark monochrome ink, remain firmly attached. Although executed entirely in black ink, the variety of ink tones makes the painting appear more real and alive.

The grape, not indigenous to Korea, was considered rare and exotic. According to the Chinese book Bowuzhi, Zhang Geon brought the plant to China from the Middle East in about 128 BC.[1] It seems that the grape plant was imported to Korea through China; however, the exact date of its introduction to Korea is unknown. Because of their rarity and exotic associations, fresh grapes and grape wines were regularly presented by rural governors to the royal court as gifts. During the late Joseon dynasty, it was popular among scholars to send gifts of grape wine or fresh fruit to friends. The grapevine motif was frequently used to decorate ceramics during both the Goryeo and Joseon periods. Among the general population, the subject of grapes was popular as a symbol of fertility: because the fruit grew in large clusters of many individual grapes, the plant came to represent the wish for many sons. The leaves in the LACMA painting have five points, suggesting that it is the wild species Vitis thunbergii with its characteristic blackish fruit[2] (det. 1).

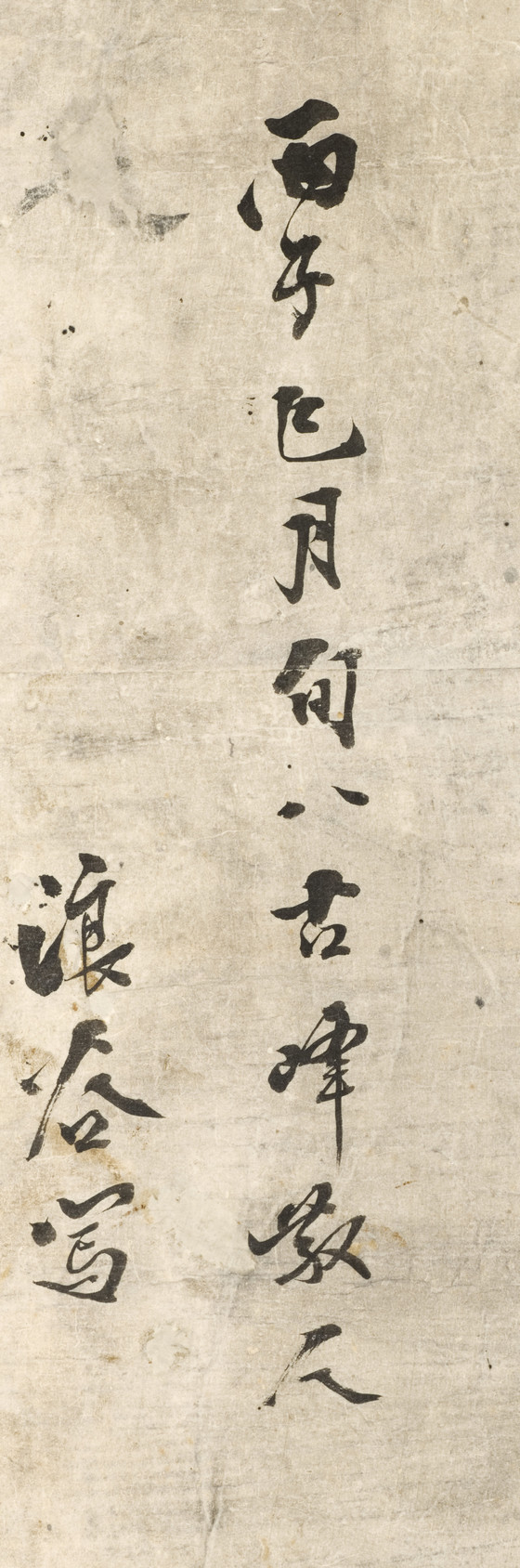

On the last panel of the screen, the artist Choi Seokhwan dated the painting 1876, and signed his pen name, Langok (det. 2). Choi Seokhwan, whose biography is not recorded, produced numerous paintings exclusively of grapevines; more than fifteen screens of his grapevines are extant today. LACMA’s example is quite typical of his style, with the S-shaped wavy vine, flying leaves, and long, dark grapes. When compared to another of his paintings of this subject in the National Museum of Korea, it is apparent that Choi repeated the same composition, ink application, and style (fig. 1). The use of the grapevine as an independent subject for paintings was largely initiated by the scholar-artist Hwang Jipjung (born 1533) during the early Joseon period.[3] In contrast to paintings by Hwang, who preferred close-up details of the plant, Choi captured the movement of long sections of vine.

An inscription added later by a collector fills a section of the screen that had been damaged (det. 3).[4] According to this passage, the collector acquired the screen in the winter of 1895:

When I returned from the capital, it was fall of the year of eulmi (1895). I had just gone through chaotic turmoil. The buildings were damaged. The windows could not block or shield the wind and the walls were cold. I went to an old shop and found a screen. The shop owner said that he had purchased it when he was in middle age and did not know who had painted it. The whole screen is painted with big lively grapevines and abundant grapes. It is truly a masterpiece. I carefully examined the signature on the screen, and I think it was done by Langok [Choi Seokhwan]. I then realized that his fame is not undeserved. So I fixed and glued the broken part of the screen with paper to protect myself against winter. I loved the painting and did not want to discard it. A guest saw me and said, “Sir, you are a man of letters. You should mount it with fine silk and decorate it with embroidery. How come you are destitute like this?” I said, “It is commonly known that there are few literati in the world. What do you think a man of letters should be? Fine silk and embroidery are praised by wealthy people, and grapes are loved by lofty people. Is a literatus identified by wealth? Or is a literatus identified by loftiness? Your idea of a scholar seems to be incorrect.” The guest did not respond. I then wrote down the incident and continued, “Eight panels and one grapevine; the leaves and fruit are abundant. I fixed the screen and used it for winter. It defends against the cold; it covers the emptiness. I make good use of it instead of storing and saving it. A gentleman stands for the middle way.”

This inscription is fascinating because it discusses both the practical function of the screen – for blocking the wind and decorating the room – and a scholar’s viewpoint on screens and their subject matter. His comments suggest how collectors from varying classes and with varying artistic values appreciated the screen differently, as evident in their preferences in mounting and display. The LACMA screen, a beautiful example of Choi Seokhwan’s energetic monochrome ink style, is especially interesting because of this inscription, which documents the attitudes of a past collector as he reflected on the subject, the practical uses of the screen, and the world around him.

Footnotes

[1] Zhang Hua, Bowuzhi (Taibei: Yiwen, 1967).

[2] Encyclopedia of Korean Culture [Hanguk minjok munhua daebaekgua sajeon], vol. 23, 547.

[3] For more about Hwang Jipjung’s painting, see Ahn Hwijoon, ed., Gukbo 10 (Seoul: Aegyung, 1984), 90.

[4]Further studies will verify the collector’s name and inscription date.

More...