Curator Notes

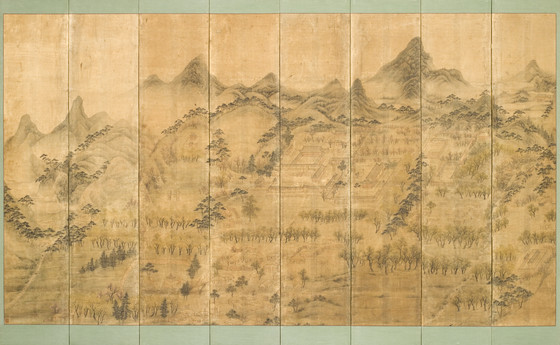

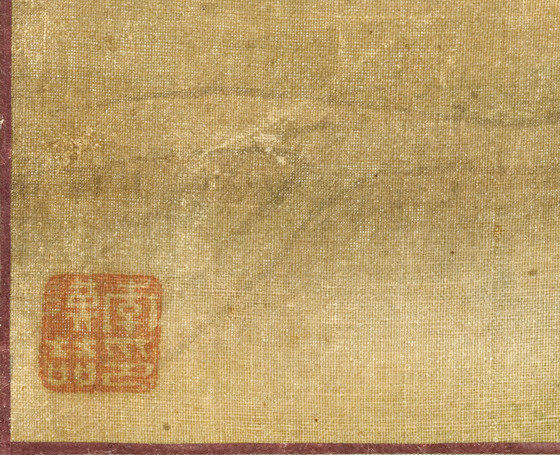

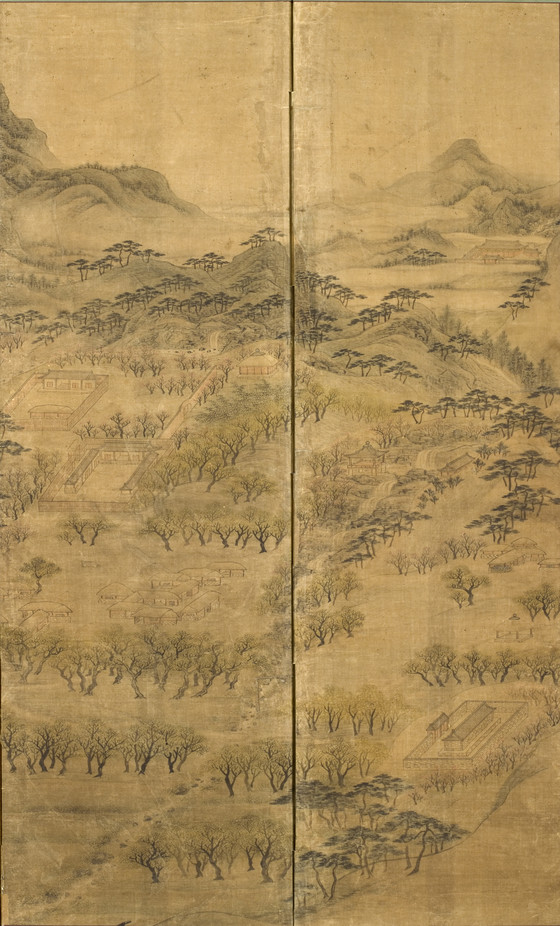

Skillfully executed with topographical accuracy, this beautifully painted screen depicts a private villa complex surrounded by mountainous scenery. An unusual example because it is mounted as a screen, the painting appears to document the importance and beauty of the estate. By the famous nineteenth-century court artist Yi Hancheol – his seal can be seen in the lower left corner – the painting may have had a specific function or purpose related to the court and royal family.

Distinct geographical and architectural similarities, as well as a close relationship between the artist and the property’s royal owner, suggest that the pavilion was in fact the Seokpa Villa (literally “Rock Hill”). Seokpa Villa was named by Yi Ha’eung (1820-1898), the Daewongun,[1] after he acquired the property around 1864.[2] Located in Bu’amdong Jongrogu, just outside Seoul’s old walled city, the area is surrounded by mountains. There were many famous villas and pavilions in the vicinity owned by powerful court officials in Seoul. Because of the area’s historical importance and natural beauty,[3] it was depicted by several famous painters during the Joseon period.

Seokpa Villa had long been in the possession of the Kim family of the Andong branch, which enjoyed enormous political influence. The Andong Kim family produced many talented officials during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and the family furthered its political ambitions by marrying the daughters to men of royal lineage. Before rising to power at court, the Daewongun already had an antagonistic political relationship with the rival Andong Kim clan; after his son’s succession to the throne, the Daewongun began systematically to suppress the members of the Andong Kim family. The confrontation between the two accelerated after Kim Heunggeun, a Chief State Counselor during the previous regime, publicly announced that there could not be two kings, clearly implying that the Daewongun should not be regent.

The Daewongun had an ambitious goal of acquiring the Kim family’s properties, particularly Seokpa Villa, and he devised a cunning strategy to achieve this. The Daewongun asked Kim Heunggeun to lend him the villa for just one day. It was a long-established Seoul custom among scholars that such a request could not be rejected. Having thus obtained the permission of the reluctant Kim, the Daewongun spent a night at the villa accompanied by his son, King Gojong. Because any place the king slept was automatically considered to be royal property during the Joseon period, the villa became a possession of King Gojong and, naturally, of his father, the Daewongun. After acquiring the villa around 1864, the Daewongun renamed it Seokpa, because of the many large rocks nearby. Seokpa was also the Daewongun’s pen name.

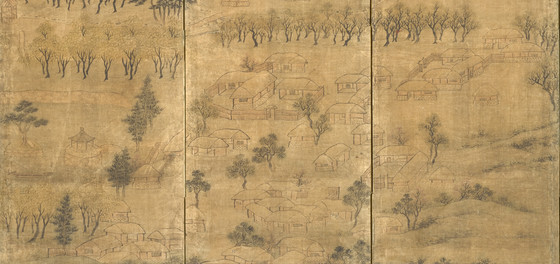

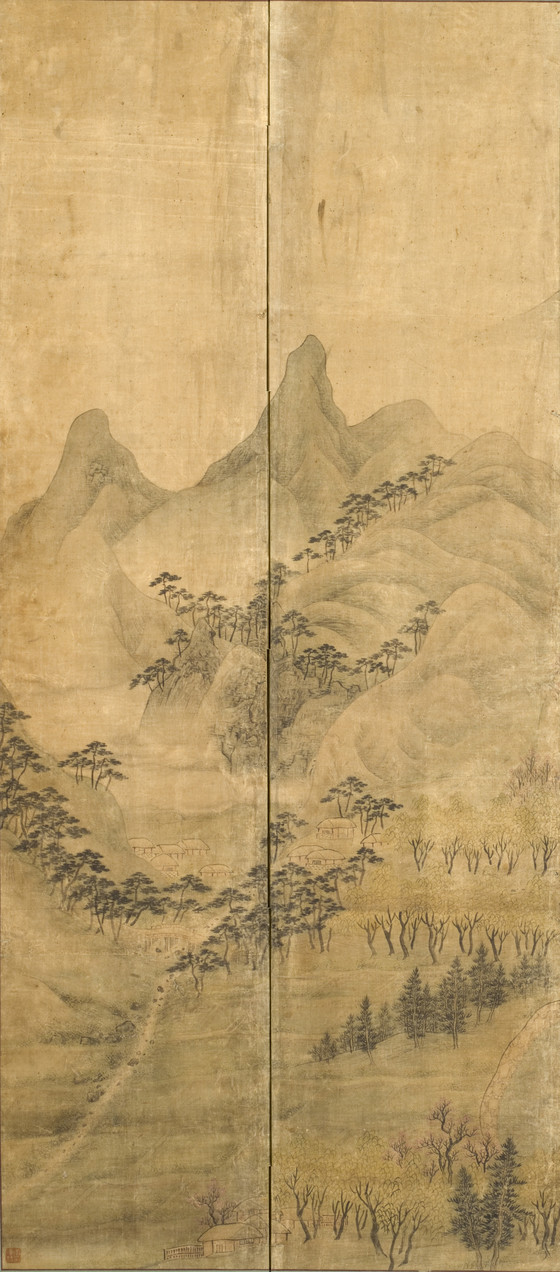

Located outside the north gate of the walled city of Seoul, Seokpa Villa was conveniently close to Gyeongbok Palace, the main imperial palace complex that had recently been rebuilt under the direction of the Daewongun. The villa is situated on the edge of Mount Inwang, the famous rocky mountain in the western part of historic Seoul, and faces Mount Baekak, the mountain that embraces Gyeongbok Palace. Both can be seen in Yi Hancheol’s painting. Visually, the screen invites the viewer to travel through the landscape to tour the villa, and the artist faithfully followed the architectural plans in his portrayal of the property. The hill with the stream, on the left, leads to the villa’s entrance gate. Past the gate are the inner quarters of the complex – distinguished by an unusual square layout – and the master’s quarters can be seen at the rear (det. 1). On the northern side of the inner quarters, there is an annex building with an attached pavilion (det. 2).

Born in 1812, Yi Hancheol was, like his father Yi Euyang, a nineteenth-century court painter of the middle rank (Jung’in), who was famous for his portraits. According to written records, Yi Hancheol executed several royal portraits, including those of King Heonjong in 1846, and two portraits of King Cheuljong, in 1852 and 1861, respectively. It is also recorded that the artist participated in a painting of King Gojong and several portraits of the Daewongun. The Daewongun and Yi Hancheol clearly knew each other because they were both active participants in the art circle led by Kim Jeonghui (1786-1856). Kim Jeonghui was the most influential academic leader and patron of the arts during the nineteenth century, introducing to Korea the epigraphy and historiography of Qing dynasty China. It is noteworthy that the circle around Kim consisted of artists and scholars from different classes: the Daewongun, of royal lineage, and Yi Hancheol, a middle-class artist, mingled in the same group. Considering the many connections between the two men, it is evident that the patron and painter had a close relationship, and it would have been natural for the Daewongun to ask Yi Hancheol to paint his favorite property, Seokpa Villa.

The Daewongun probably commissioned this screen both to record his ownership of the villa and to appreciate the beauty of the estate. Paintings of private property are not unusual in East Asia. In Korea, from the mid-Joseon period, many officials and scholars began to obtain private villas and pavilions in scenic locations, and paintings of estates were produced in large numbers. A representative example of this is Hermitage of the Recluse, Seokjeong, painted by Jeon Chunghyo in the seventeenth century (fig. 1). Although presented in different formats – Jeon’s painting is a hanging scroll – the overall layout of the property is similar: mountains surround the villas and the primary housing complexes are located near the center of the composition. Both artists showed a fine attention to detail in their treatment of the architectural elements. Although there are some differences in the artists’ painting styles – in the depiction of the mountains and application of brushstrokes – the purposes of the two paintings are similar and both clearly function as records of the property.

Paintings of private estates were typically created in a hanging scroll or album format, so the LACMA screen is significant. When, in rare cases, they were painted as screens, each panel typically depicted an individual scene within the property, as in Eight Views of Musudong (fig. 2) or Landscapes of Hawoe (fig. 3). The continuous, expansive view of the estate in the LACMA painting suggests the importance of Soekpa Villa and the owner’s affection for it.

LACMA’s screen, an excellent example of nineteenth-century estate painting, is invaluable to our understanding of the work of Yi Hancheol, of court painting and patronage, and of the function of estate paintings. The quality, format, and scale of the painting demonstrate that the Daewongun had the wealth, power, and intent to commission such a major project.

Footnotes

[1] The Daewongun is an official title given to the father of a king who ascended the throne, but who was not a son of the preceding king. Yi Ha’eung, the Daewongun, was the father of King Gojong, who succeeded to the throne at the age of twelve and reigned from 1864 to 1907. King Gojong was the second to last king of Korea, and, as such, he witnessed the national turmoil brought about by Korea’s modernization and Westernization. The Daewongun, father to this young king, soon became regent, and he began to introduce substantial reforms in every field during the early years of his son’s reign, from 1864 to 1873. The Daewongun made every effort to reestablish the reputation and power of a court that had been weakened by corrupt members of the royal family and self-serving scholar-officials.

[2] According to Huang Hyon in the Alternative Histories by Maechon [Maechon yasa], the Daewongun acquired Seokpa Villa around 1864.

[3] Today, the land surrounding of the villa is not so pristine. The area was recently released from the so-called greenbelt regulation, and the hill below the villa has been parceled for modern construction. The property now belongs to a private owner and is never open to the public. Until the Korean War, the descendents of the Daewongun had owned the villa; during and shortly after the war, it served as an orphanage. Since that time, it has passed through several private owners. In 2006, the property, which is still registered as Cultural Heritage Site Number 26, was put up for auction. The land itself comprises eleven acres and has not been approved for development because of its cultural heritage status. It most recently sold for $6.9 million.

More...