Curator Notes

This eight-panel screen illustrates in brilliant color the legendary banquet that Xiwangmu held for the immortals around the Jasper Lake, known as yojiyeon in Korea. Because Korean scholars and artists frequently looked to China for inspiration, many Daoist subjects naturally came to appear in Korean painting. In the Daoist tradition, the Queen Mother of the West, Seowangmo (Chinese: Xiwangmu), was believed to dwell in a beautiful palace made of precious stone. The palace, high in the Kunlun mountains, was surrounded by a lush garden, and in this garden grew the famous peaches of immortality that bore fruit once every three thousand years. In later accounts, Queen Mother Seowangmo is accompanied by her consort, the King Father of the East, Dongwanggong, who was the father of her children and who reportedly maintained a register of the Daoist immortals.[1] Together, the Queen Mother and King Father embody cosmic harmony and the unity of yin and yang, the two primary principals essential to East Asian philosophy. The Queen Mother represents the dark female yin, while the King Father represents the masculine yang energy. According to legend, she held an impressive banquet for the immortals every three thousand years to celebrate the ripening of the peaches.

Literary references to her abound and many stories describe her visiting or greeting earthly rulers who desperately sought immortality, such as her famed meeting with King Mu of the Zhou dynasty (c. 1050-221 BC).[2] In later Chinese painting, the subject of the Queen Mother of the West appears frequently in many forms and painting formats. As a goddess of immortality, she is depicted individually as a subject of worship and also as a part of larger sets of paintings depicting the extended Daoist pantheon. Other representations include the Queen Mother riding a fantastic animal through the sky or regally seated at the center of her court.

In this painting, Queen Mother Seowangmo and her consort Dongwanggong are enthroned at the center of a garden terrace surrounded by peach trees heavy with fruit overlooking the Jasper Lake (det. 1,2). Beautiful maidens make final preparations for the banquet and musicians accompany a dance performance featuring a pair of phoenixes (det. 3). As the banquet commences, the many illustrious and immortal guests can be seen on the three panels at the far left, descending from the sky on clouds or floating across the water. The great Daoist philosopher Laozi is the first guest to enter the gathering (det. 4). He is riding a water buffalo, and he can be seen at the bottom of the sixth panel from the right. Close behind him, crossing the water, are the Eight Immortals. He Xiangu, with a basket of mushrooms; Li Tieguai, with his crutch; Zhongli Quan, with his robe open; Lü Dongbin, with a sword; Han Xiangzi, with a flute; Zhang Guolao, with his musical instrument; and Lan Caihe and Cao Guojiu.[3] The popular god Shoulao, distinguishable by his protruding head, and a goddess with a rabbit, presumably representing the moon and feminine yin force, can be seen in the clouds directly above (det. 5). Perhaps most interesting, at the top of this group is a monk accompanied by four warriors, apparently a reference to the classic Korean novel A Dream of Nine Clouds by Kim Manjung (1637-1692). In the novel, the monk Shaoyu (literally, “brief sojourner”) “dreams” of being tempted and returning to a mortal life only to “wake up” to find Paradise by realizing that all life is illusion. In this painting, the subject of the banquet of Seowangmo takes on a uniquely Korean form: Not only was the subject modified to fit the screen format so popular in the late Joseon period but the artist depicts non-Chinese characters, including a character from a popular Korean novel.

In the poem “Rhapsody of Hanyang [Seoul],” the writer describes the vibrancy of Seoul in 1822, commenting on the city’s geography, culture, customs, and even royal activities. The poet also mentions that art dealers around the Gwangtong bridge sold screens featuring the banquet of Seowangmo. The subject of this banquet appears to have been very popular in later Korean painting. It was apparently a theme chosen, even by the royal court, to celebrate birthdays and other special occasions. One known screen depicting this subject created to celebrate the installation of a crown prince who would later be named King Jeongjo (fig. 1). This royal screen, now missing two panels, displays the same iconography and features as the LACMA screen.[4] During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the theme was also popularly used in folk paintings; several unsigned versions of the Banquet of Seowangmo, Queen Mother of the West have survived.[5]

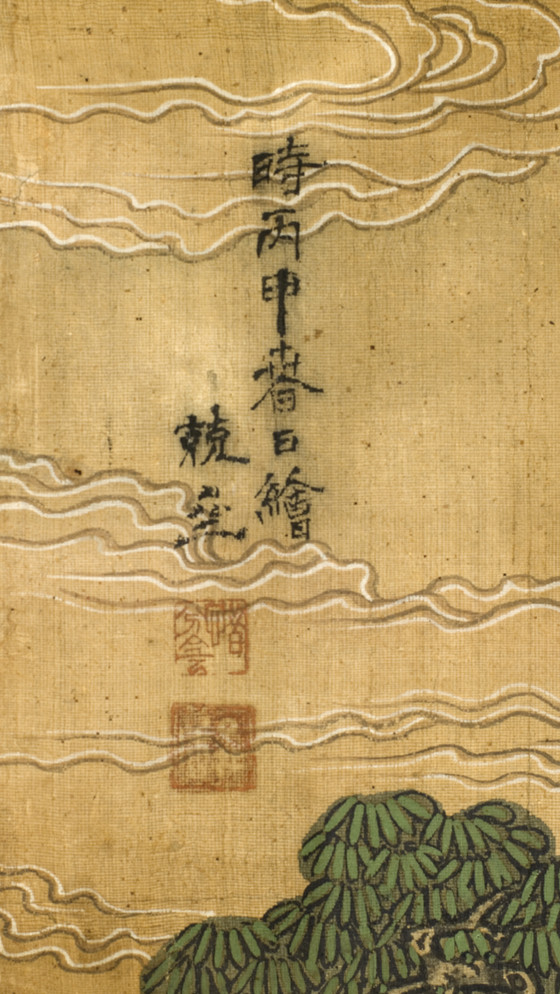

On the last panel on the left (det. 6), there are two seals (one is illegible) in addition to a one-line inscription that reads, “painted in the year of byongsin, by Geungje.” Geungje is the pen name of a famous genre painter, Kim Deuksin (1754-1822), who was praised for his expertise in figure painting. However, the first seal does not belong to Kim and the calligraphy on the inscription is notably different from the inscriptions on paintings by Kim Deuksin known to be authentic. Further study is necessary to identify the painter and the date of the LACMA screen.

Footnotes

[1] Dongwanggong does not appear until the Han dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) and replaces earlier cosmological symbols representing yang. See Wu Hung, “Xiwangmu, the Queen Mother of the West,” Orientations 18, no. 4 (April 1987), 24-33.

[2] For a comprehensive early history of Xiwangmu through early textual evidence up to the Tang dynasty, see Suzanne E. Cahill, Transcendence and Divine Passion: The Queen Mother of the West in Medieval China (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1993), 11-65.

[3] The Eight Immortals, a celebrated group of popular Daoist spirits each with its own tales and attributes, were first worshipped in the Song dynasty (960-1279). For more on the immortals, see C.A.S. Williams, Outlines of Chinese Symbolism and Art Motives (Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1976), 151-56. Regarding their first appearance in the Song dynasty, see Steven Little, Realm of the Immortals (Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art, 1988), 10-11.

[4] Seoul Museum of History, Happy! Joseon Folk Painting [Bangapda wuri minhwa](Seoul: Seoul Museum of History, 2005), 66.

[5] A similar ten-panel screen was sold at Sotheby’s New York; June 18, 1993 (Sale 6441, Lot 34).

More...