A nahan (Chinese: lohan; Sanskrit: arhat) is a disciple of Buddha who has reached enlightenment. Nahans are generally deified in groups of sixteen, eighteen, or five hundred....

A nahan (Chinese: lohan; Sanskrit: arhat) is a disciple of Buddha who has reached enlightenment. Nahans are generally deified in groups of sixteen, eighteen, or five hundred. Among these groups, the Sixteen Nahans were considered to have the greatest supernatural powers during the late Joseon period. According to the Record of the Abiding by the Dharma Spoken by the Great Nahan Beopjugi[1], the mission of the Sixteen Nahans was to benefit sentient beings and protect the Buddha’s righteous teachings; they could not enter Nirvana until the Buddha Mireuk (Sanskrit: Maitreya) came into this world. The Beopjugi gives the names of the Sixteen Nahans, the places they stayed, and the number of their followers; however, it does not describe their appearance. When depicting them, artists adopted the images of Buddhist disciples, freely expressing their poses, garments, and other props. This was also true for depictions of the Eighteen Nahans and the Five Hundred Nahans.

Artists in China were the first to create paintings of nahans. After Monk Hyeonjang translated the Beopjugi in 645, as Buddhism was flourishing in China during the Tang dynasty (618–906), the belief in nahans became more widespread and depictions of them became more common. In Korea, paintings of the Five Hundred Nahans were more popular during the Goryeo period, while paintings of the Sixteen Nahans were more popular in the late Joseon period. In the late Joseon period especially, the number of paintings created to depict the Sixteen Nahans was based on the size of the Nahan Hall where the paintings were to be enshrined. If the hall was large enough, the artist would create eight separate paintings, each featuring two nahans.

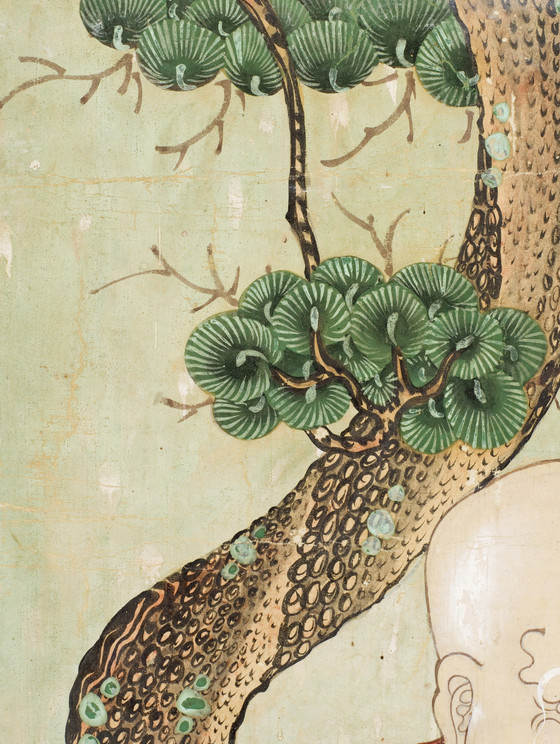

In this painting, the nahan on the left, holds a wish-granting jewel (Korean: yeouiju; Sanskrit: cintamani) in his left hand and a small dragon in his right (det. 1, 2). The depiction of a nahan holding these attributes has a long history that dates back to the Song dynasty (960-1279) in China. According to the Chinese book Stories of High Monks, when there was drought, the high monk called for the dragon and made the rain fall; in nahan paintings, a dragon typically appears from the sky or from water. The composition seen here, in which the nahan holds the dragon in his hand, was more common in paintings from the late Joseon period (1700-1850).

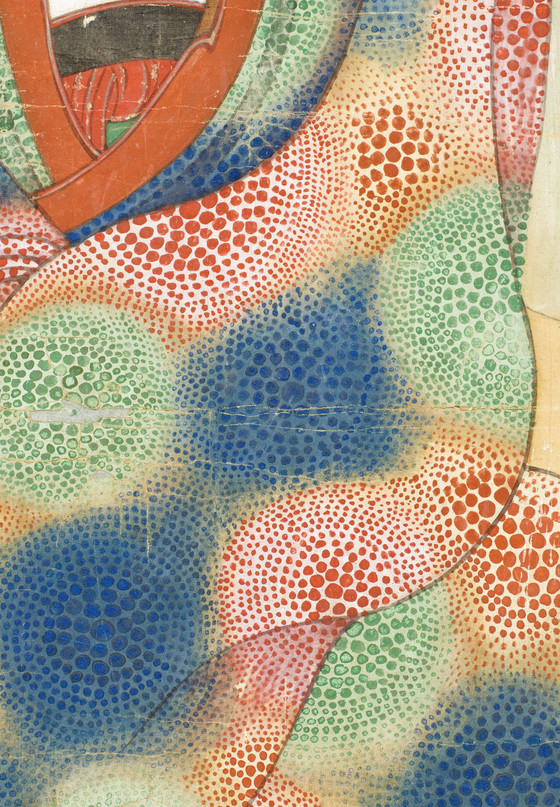

The nahan on the right, wears a cowled robe that covers his head and body, a portrayal based on images of monks at the highest level of meditation (Korean: seonjung; Sanskrit: Samadhi). The best early examples of this portrayal are the carved sculptures in the Yungang Caves, which date from the Northern Wei period (386-534/5) of China, and the murals of monks (bigus) in the Dunhuang Caves, from the Western Wei period (535-556) of China. The robe seen here has a pattern of large concentric circles that are composed of red, green, and blue dots (det. 3). This pattern is only found in the late Joseon period.

The vividly painted nahans in this painting fill the canvas and they are solid and well-proportioned. Contour lines were created with a brown pigment. The frowning nahan on the left has a distinctive wrinkle between his eyebrows, and white facial hair. The nahan on the right has a more placid expression, and his eyebrows are thin and curved like a bow. This characteristic can mainly be observed in nineteenth-century Buddhist paintings from Gyeongsang province.

The LACMA painting is very similar in size, style, and composition to a set of seven paintings featuring the Sixteen Nahans from 1862 currently in Yuga Temple in Daegu, North Gyeongsang province (fig. 1). It is believed that the LACMA pair of nahan paintings might once have been part of this set. The image also resembles Buddhist paintings by Gyeong Dam Seong Gyu (active 1850-1860), and it is possible that it was painted by his school of artists. Furthermore, Haeun Eungsang’s painting Sixteen Nahans from 1884 at Yongmun Temple (fig. 2) and the late-nineteenth-century painting of Sixteen Nahans at Hae’in Temple show additional similarities in style with this work.

Footnotes

[1] The Record of the Abiding by the Dharma Spoken by the Great Nahan Beopjugi (Sanskrit: Nadimitra; Korean: Dae arahan nanjemil dara soseol beopjugi; hereinafter, Beopjugi).

Bibliography

Shin Kwang-hee. “A Study on Iconography of Nahan in Meditation.” Munwhasahak 27. Culture History Association of Korea, 2007.

———. “A Painting of the Sixteen Nahans in Heungguk Temple, Yeosu.” Misulsahak yeongu 255. Art History Association of Korea, 2007.

More...