Curator Notes

A Buddhist patriarch (josa) is an ascetic who works for the salvation of all sentient beings, awakening others to the enlightenment of Buddhist doctrine through cultivation and practice. According to the Collection from the Patriarchs’ Hall,[1] a compilation published in 952 that includes stories associated with the patriarchs, there are thirty-three Buddhist patriarchs: twenty-eight are Indian patriarchs (from the first patriarch, Mahagaseop, to the twenty-eighth patriarch, Bodhidharma [Korean: Bolidalma]), and six are Chinese patriarchs. Although this adds up to thirty-four, the total number of patriarchs is considered to be thirty-three because Bodhidharma, the twenty-eighth Indian patriarch, is also the first patriarch of Chinese Chan (Korean: Seon; Japanese: Zen) Buddhism. He is counted once.[2]

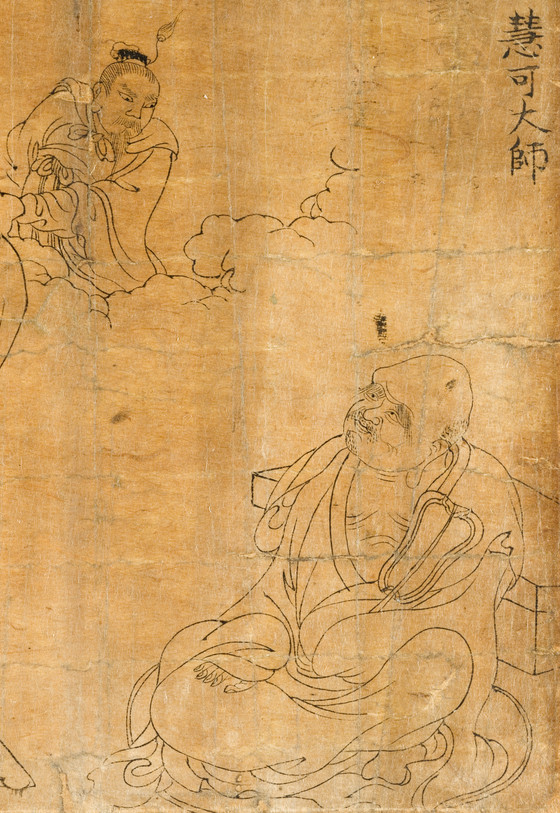

The Collection from the Patriarchs’ Hall also records that Huike (487-593; Korean: Hyega),[3] the second Chinese patriarch, was a disciple of the first patriarch Bodhidharma. According to legend, Bodhidharma at first refused to allow Hyega to become his disciple. In order to prove his seriousness and commitment, Huike cut off his own left arm and offered it to Bodhidharma, who was sitting in meditation for nine years facing the wall of a cave.

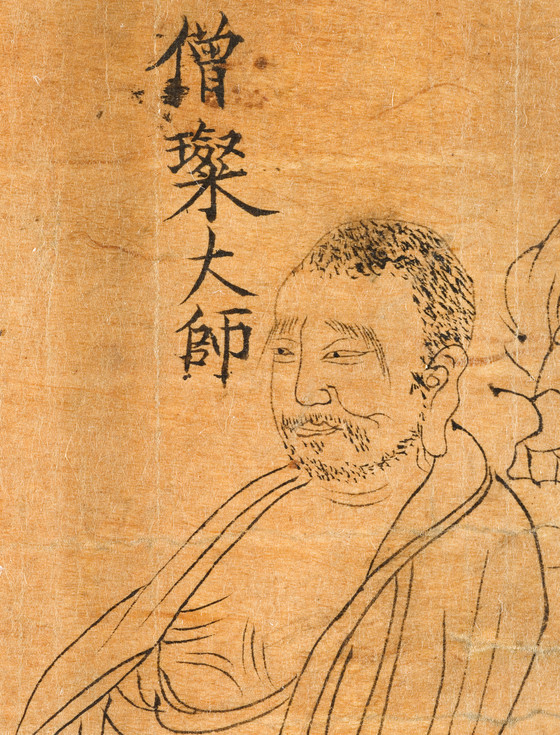

According to tradition, the third Chinese patriarch, Sengcan (died 606; Korean: Seungchan), awakened to enlightenment after engaging in a seonmundap – a series of questions and answers used as an aid to attaining enlightenment – with Huike. Seungchan then became Huike’s disciple.

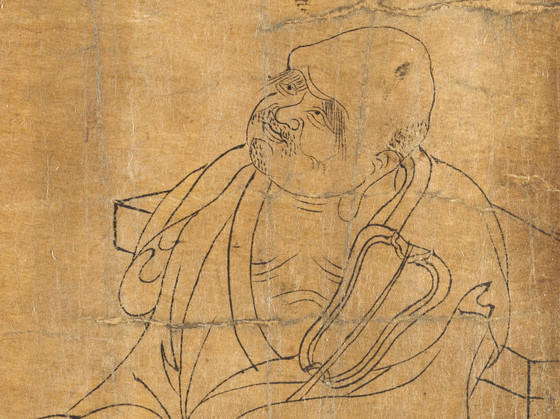

The fourth Chinese patriarch, Dao Xin (610-674; Korean: Dosin), was a disciple of Seungchan. According to legend, the Chinese emperor Taizong (Korean: Taejong) several times requested that Dao Xin travel to his palace in the capital to preach. Each time, Dao Xin refused. Finally, the emperor told his messengers that if Dao Xin refused again, they were to cut off Dao Xin’s head. When the messengers related this to Dao Xin, he calmly stretched out his neck toward their swords. Instead of cutting off his head, the stunned messengers returned to the emperor to report what Dao Xin had done. The emperor respected Dao Xin even more after this.

This drawing, which depicts Huike, Sengcan, and Dao Xin, originally included all thirty-three patriarchs and appears to be a preparatory sketch for a color painting. Huike, the second patriarch, can be seen sitting in the lower right corner (det. 1). He is holding a fan and looking at the messenger, who is riding on the clouds above. Sengcan, the third patriarch, stands in the center (det. 2). His left hand rests on his right palm in front of him; behind him can be seen a crane. Dao Xin, the fourth patriarch, is on the lower left. He sits on a cushion and bends forward, looking at the floor (det. 3). The inscriptions on the drawing identify each of the patriarchs by name.

During the late Joseon dynasty in Korea, many paintings of the thirty-three Buddhist patriarchs were modeled on Ming dynasty prints. This drawing appears to be based on illustrations found in two Chinese books – Assembled Pictures of the Three Realms (San ts’ai Tu hui) and Hong shi xian fo qi zong – which were published in the Wanli period (1573-91) during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). Comparable works depicting the Thirty-three Patriarchs exist in Seonam Temple in Suncheon, South Jeolla province, which has a painting from 1753 (figs. 1 and 2); in a private collection, which has a drawing from 1768 (fig. 3); and in the Hall of Amita (Sanskrit: Amitabha) Buddha in Cheoneung Temple in Gurye, South Jeolla province, which has a late-eighteenth-century wall painting.

While the depiction of the patriarchs in the LACMA drawing and the Seonam Temple painting is similar, some elements are different; for example, in the Seonam Temple painting the crane next to Sengcan is omitted and a messenger with a sword is in front of Dao Xin, trying to cut off the patriarch’s head. The drawing from the private collection, of which four panels currently remain, portrays Shakyamuni with the thirty-three Buddhist patriarchs. The portrayals of Huike and Sengcan in the private collection drawing closely correspond to those seen in LACMA’s drawing, except that in the private collection drawing, the artist has included bridge railings and bamboo behind Sengcan.

This type of drawing, which was usually used as a preparatory sketch for a painting, was widely produced as artists copied and illustrated sutras that transmitted Buddhist ideas and doctrines. The process, in which an artist traced an original work of art into an ink outline drawing, was closely related to the illustration of Buddhist texts. Through this procedure, artists learned traditional iconography while they also created new iconography that reflected the social and cultural influences of the period. Artists shared these drawings with each other, which led to the creation of Buddhist paintings with similar compositions, forms, and motifs.

In the LACMA painting, the same iconography is found not only in paintings of the thirty-three patriarchs but also in paintings of nahans (Sanskrit: arhats). The iconography of patriarch Huike is also found in a set, Sixteen Nahans from 1723 in Heungguk Temple in Yeosu, South Jeolla province, and a painting from 1725 in Songgwang Temple in Seungju, South Jeolla province. Artists probably mixed iconography when depicting nahans and Buddhist patriarchs because there was no common, established tradition governing the portrayal of these two different groups of Buddhist figures.

The LACMA drawing is important for a number of reasons. It shows a close relationship with Ming dynasty prints, such as those found in the Sancai tuhui, and the important process of sketching to the transmission of Buddhist iconography into Joseon dynasty paintings. Its inscriptions give the names of the patriarchs, making it possible to identify the figures.[4] In addition, very few of these preparatory sketches are currently known to exist. LACMA’s sketch was recently restored and is in excellent condition.

Footnotes

[1] In Chinese, the title is Zutang ji; in Korean, Jodangjip.

[2] When Buddhism spread from India into China, Chinese Chan (Korean: Seon; Japanese: Zen) Buddhism developed its own patriarchs. Because Bodhidharma was the first Indian patriarch to reach China, he is considered the first patriarch of Chinese Buddhism. At the same time, he is the twenty-eighth patriarch in the much older lineage of Indian Buddhism.

[3] This essay uses the Chinese Buddhist lineage for the patriarchs. The names of the patriarchs vary from country to country. This essay uses their Chinese names throughout.

[4] It appears that, at one time, the name of the second patriarch, Huike, which appears in the upper right corner, was rewritten and moved slightly to the right.

Exhibitions

Drawing on Faith. Seoul, KOR, Dongguk University Museum; Los Angeles, CA, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, August 21, 2003 - January 11, 2004.

More...

Bibliography

- Wilson, J. Keith. "Korean Art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art." in Korean Art: Articles from Orientations 1970-2013, edited by Yifawn Lee and Jason Steuber, 428-35. Hong Kong: Orientations Magazine Ltd, 2014.

- Korean Art Collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, U.S.A. Daejeon, Republic of Korea: National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage, 2012.