Curator Notes

John Frederick Peto (1854-1907) was born and raised in Philadelphia. He espoused a highly realistic style of painting that reflected the period's rationalism and concern for materiality, an aesthetic in opposition to the freer and individualistic handling of paint of the contemporaneous impressionists. In the late 1870s, Peto entered the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where he became friends with William Harnett, recently returned to the academy after several years in New York City. It was about this time that Harnett began exhibiting his mature illusionistic still lifes. Although most still life painters aim to be convincingly realistic, Harnett went beyond mere imitation, often to the point of deception. These still lifes made Harnett’s fame and spawned a virtual movement of followers.

Peto considered Harnett his "ideal of perfection in still life painting," and as Harnett, specialized in still lifes, both table-top compositions and trompe l’oeil ("deceives the eye"). Yet Peto was no mere imitator. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Peto did not consider the visual trickery and illusion so often associated with works of trompe l’oeil as the sole aim of his art. In Harnett’s paintings, objects were depicted so realistically that many people actually had to touch the canvas before they were convinced that the objects they were seeing were painted, not "real." Peto, however, was more concerned with the manner in which light could affect an object rather than with the precise rendering of that object, and his canvases have a softer, less hard-edged style.

Peto left Philadelphia in the late 1880s, marrying Christine Pearl Smith and spending the rest of his life in Island Heights, New Jersey, away from the cosmopolitan art centers. His painting had received little recognition in Philadelphia, and Peto ceased to promote his work after settling on the New Jersey shore. In Island Heights, Peto and his wife made at least part of their living through Peto’s cornet playing and by running a summer boarding house for vacationers. Peto continued painting, and many of his works including smaller still lifes are presumed to have been sold to these boarders as souvenirs.

Harnett and most of his contemporaries delineated in their still lifes finely bound books, musical instruments, vases, handsome stationery, and other objects that were emblematic of – and therefore more salable to – a wealthy and educated class. Peto, on the other hand, depicted humbler objects – torn envelopes, broken latches, inexpensive pottery, and burnt matches. Scholars have suggested that his decision to concentrate on "banal" subject matter had much to do with the lukewarm reception his work received during his lifetime; neither buyers nor critics felt that these ordinary objects were models worthy of artistic reproduction. With time Peto’s canvases took on more personal associations and became even more distinctly darker palette and more modest objects, older and worn, arranged in a state of disarray, perhaps indicative of Peto’s way of life as well as his frustration over the failure of his art to garner critical praise and an appreciative audience.

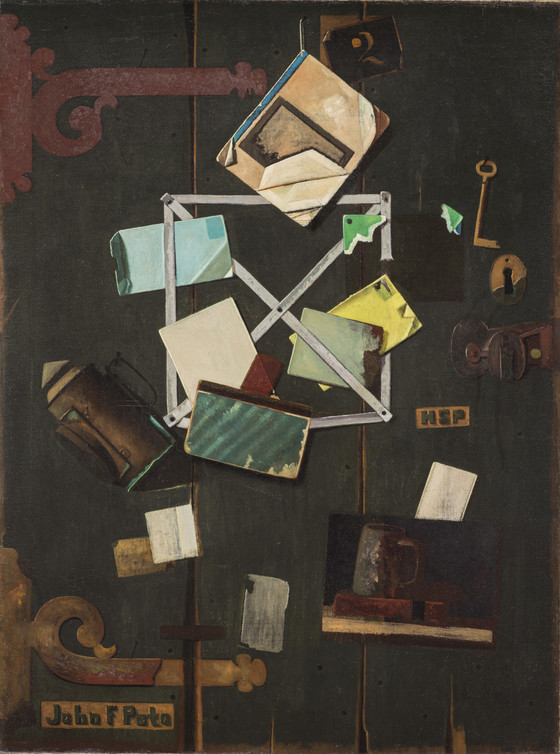

"Rack pictures" such as this one comprised a large part of Peto’s oeuvre from 1879 to 1904, and he was a master of this type of trompe l’oeil composition. The term "rack" refers to the practice – common in business offices at the time – of affixing to the wall or a board a square of cloth tape with additional cloth-tape crosses inside. Notes, mail, advertisements, and miscellaneous objects were then tacked on to the tape. The rack picture offered Peto a unique challenge in trompe l’oeil, because he had to create the illusion that actual objects were in a narrow, almost flat space. Peto’s rack pictures can be divided into two distinct periods, the first dating between 1879 and 1885 and the second between 1894 and 1904. The racks in the early works have more complex tape grids, with some of the details of the objects elaborately conveyed; the objects also show less deterioration. HSP’s Rack Picture is from the latter period, during which Peto’s work became increasingly subjective. These later works are characterized by dark green or brown backgrounds and by single squares of crossed tape that were more frequently frayed and torn.

HSP’s Rack Picture, one of Peto’s bigger paintings, is the largest of the rack pictures and represents the culmination of his work in this genre. It incorporates many elements familiar from his earlier paintings, such as the hanging lantern, key, old books, envelopes, and a small oil sketch of a book and a mug. New to this work are the large wrought-iron hinges, their rough texture and curving silhouettes animating the composition. Although painted, the artist’s signature as well as the initial "HSP" appear to be cut into a painted wooden backboard, thereby heightening the illusion of an actual business rack. Peto authority John Wilmerding has described the painting as "one of Peto’s most beautiful and poignant late works, in which the muted colors and worn elements convey a restrained sense of sad discomfort. The artist was then suffering the pain of Bright ’s disease, and the strong solid letters of his daughter’s initials indicate how important a place she occupied in his family life. The painting is about the salvaging of order and beauty in the face of anxiety and collapse."

Although the initials, HSP, refer to Peto’s only daughter, Helen Serrill Peto, there are fewer explicit individual references than in earlier rack pictures. Rack pictures that were private commissions often included personalized details that could be related to that person or business, such as an envelope address, a printed advertisement, or letterhead. While many of his contemporaries would have delineated the script in the addresses of envelopes or advertisements, Peto omitted these details. The stationery in HSP’s "Rack Picture" became simple rectangular shapes or color, elemental parts in the overall design of his composition. Peto had moved away from strict representation, and design became his primary focus. He began to conceive of his painting in more formal, abstract terms, and this additional dimension removes the work from the 19th-century trompe l’oeil and places it within the birth of 20th-century modernism.

Harnett’s work was resurrected in the 1930s when commercial dealers and art historians found new interest in realist art from the preceding century. A decade later, in the late 1940s Peto’s work was rediscovered by Alfred Frankenstein, a Northern California-based art critic. Frankenstein unearthed unusual discrepancies in both the style and the subject matter of paintings that had been attributed to Harnett. Through diligent and exhaustive detective work, and with the assistance of conservation specialists, art historians, and countless individuals, Frankenstein found that nearly one-third of the works signed with Harnett’s name (probably by various dealers after his death) were in fact painted by other artists, among them John Frederick Peto. Peto’s work could finally receive the recognition it had not been afforded for decades.

In the late 1980s Peto became as popular as Harnett with collectors. He is now not only viewed as one of the principal exponents of the late 19th-century trompe l’oeil movement, but appreciated for his distinctive proto-modernist aesthetic.

Ilene Susan Fort (1998)

More...

About The Era

After the Jacksonian presidency (1829–37), the adolescent country began an aggressive foreign policy of territorial expansion, exemplified by the success of the Mexican-American War (1846–48). Economic growth, spurred by new technologies such as the railroad and telegraph, assisted the early stages of empire building. As a comfortable and expanding middle class began to demonstrate its wealth and power, a fervent nationalist spirit was celebrated in the writings of Walt Whitman and Herman Melville. Artists such as Emanuel Leutze produced history paintings re-creating the glorious past of the relatively new country. Such idealizations ignored the mounting political and social differences that threatened to split the country apart. The Civil War slowed development, affecting every fiber of society, but surprisingly was not the theme of many paintings. The war’s devastation did not destroy the American belief in progress, and there was an undercurrent of excitement due to economic expansion and increased settlement of the West.

During the postwar period Americans also began enthusiastically turning their attention abroad. They flocked to Europe to visit London, Paris, Rome, Florence, and Berlin, the major cities on the Grand Tour. Art schools in the United States offered limited classes, so the royal academies in Germany, France, and England attracted thousands of young Americans. By the 1870s American painting no longer evinced a singleness of purpose. Although Winslow Homer became the quintessential Yankee painter, with his representations of country life during the reconstruction era, European aesthetics began to infiltrate taste.

More...

During the postwar period Americans also began enthusiastically turning their attention abroad. They flocked to Europe to visit London, Paris, Rome, Florence, and Berlin, the major cities on the Grand Tour. Art schools in the United States offered limited classes, so the royal academies in Germany, France, and England attracted thousands of young Americans. By the 1870s American painting no longer evinced a singleness of purpose. Although Winslow Homer became the quintessential Yankee painter, with his representations of country life during the reconstruction era, European aesthetics began to infiltrate taste.

Label

Exhibition Label, 1997

Today considered one of America’s greatest still-life painters, John Frederick Peto excelled in trompe l’oeil painting – literally meaning paintings that “fool the eye.” Canvases such as HSP’s Rack Picture, the largest of his late paintings, were created to trick the viewer into thinking that s/he is looking at a real “card rack” tacked into a worn wooden door. In Peto’s time, card racks served in much the same way today’s kitchen or office corkboards do; advertisements, mail, and messages were slipped beneath a series of carefully arranged ribbons and held to a vertical surface for quick reference.

Peto’s highly illusionistic canvases were remarkable not only for their visual trickery, but also for their aesthetic and conceptual complexity. Often, the artist would include visual and textual clues from his rack’s everyday ephemera to piece together an elaborate narrative. In this case, however, though the “HSP” of the title, carved into the wood background, refers to Peto’s only daughter, the canvas serves more as a composition study than an allegory. Pete’s meticulous arrangements of shapes and forms – as well as his exploration of depth in life’s mundane objects – are of particular interest to contemporary art historians, who argue that his card racks foreshadow similar issues addressed in early twentieth-century abstract and conceptual art of the generation that followed him.

More...

Bibliography

- Hauptman, William. Peindre l'Amerique: les Artistes du Nouveau Monde 1830-1900. Lausanne: Fondation de l'Hermitage, 2014.

- Kim, Woollin, Jinmyung Kim, and Songhyuk Yang, eds. Art Across America. Seoul: National Museum of Korea, 2013.

- Miller, Angela, and Chris McAuliffe, eds. America: Painting a Nation. Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2013.

- About the Era.

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art. New York: Thames and Hudson, 2003.

- LACMA: Obras Maestras 1750-1950: Pintura Estadounidense Del Museo De Arte Del Condado De Los Angeles. Mexico, D.F.: Museo Nacional de Arte, 2006.

Blondet, José Luis. Six Scripts for Not I: Throwing Voices (1500 BCE-2020 CE). Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2020.