Sources: Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints - The Early Years, Helen Merritt, University of Hawaii Press, 1998, p. 240-241; Guide to Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints: 1900-1975, Helen Merritt, University of Hawaii Press, 1992, p. 133-134; 44 Modern Japanese Print Artists, Volume II, Gaston Petit, Kodansha International Ltd., 1973, p. 120 and as footnoted.

Sekino Juni'chirō is one of the major post-WWII figures in the sosaku hanga (creative print) movement. He was born in Yasukata-cho, Aomori Prefecture in northern Japan in 1914, the first son of Sekino Junzō who owned a wholesale fertilizer store. From an early age Sekino displayed an artistic bent and a fascination with Japanese woodblock prints. While still in middle school, he and a friend started a poetry and print magazine called Ryokuju-mu (Dream of Green Foliage) and at the age of eighteen he created a folio of prints depicting insects. He lived close to the great print artist Munakata Shiko (1903-1975), to whom he often turned for advice.

While largely a self-taught artist, having closely studied available material on woodblock carving and printing while still young, he did study etching at Nishida Takeo’s Japanese Etching Institute and oil painting and drawing at a private painting school. In addition, starting in 1931, he studied intaglio printmaking and lithography with printmaker Kon Junzō (1893-1944), who considered Sekino "an artistic genius."1

In 1935 the artist Okada Saburosuke (1869-1939) and the etcher Nishida Takeo praised Sekino’s etchings during a visit to Aomori and suggested that he enter the government sponsored Teiten exhibition. Sekino submitted an etching of Aomori harbor and won a first prize. In October 1935 he also won a prize for a woodblock at the fourth exhibition of Nihon Hanga Kyokai (Japanese Print Association). In 1938 he became a member of Nihon Hanga Kyokai (Japan Print Association) and in 1940, after moving to Tokyo, of Kokugakai (National Picture Association).

According to Merritt, Sekino “dreamt constantly of moving to Tokyo,” but his obligations to his family and the family’s fertilizer business kept him in Aomori until after the death of his mother and the failure of the business.1 After moving to Tokyo, in April 1939, he worked for the publisher Shimo Taro who introduced him to Onchi Koshiro (1891-1955). He became one of the original members of Onchi’s Ichimokukai (First Thursday Society), contributing to all of the group’s Ichimokushu print portfolios, and was considered Onchi’s right-hand man.

During the war, Sekino worked for the welfare department of the Iwasaki Communications Company procuring lodging and theater facilities for various entertainment troupes that came to his town to entertain the armament workers. This brought him in contact with the famous kabuki actor Nakamura Kichiemon (1886-1954), whose portrait in woodblock he was to create in 1947. This portrait of Kichiemon, heavily influenced by Onchi’s 1943 seminal work, Portrait of Hagiwara Sakutaro, is one of Sekino's most famous works, and along with portraits of the artists Munakata Shiko and Onchi Koshiro, established Sekino’s position as the leading woodblock portraitist.

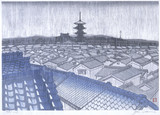

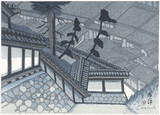

Not limited to portraiture, Sekino also portrayed cityscapes, rural scenes, animals, still lifes, landscapes, and abstract works. While most famous for his woodblock prints, Sekino also worked with lithography and etching, founding the Japanese Etcher’s Society in 1953. He also contributed to numerous book designs.

Writing in 1956, Oliver Statler wrote of Sekino’s life: “Sekino lives in one of Tokyo’s myriad little off-the-avenue residential areas, laced by unnamed, unpaved lanes and punctuated by the neighborhood bathhouse. His studio is upstairs, and when he comes down, the visitor’s first impression is of big wide eyes and a huge shock of unruly black hair. Ingenuous and friendly, he consistently manages to give the impression of fresh pleasure with the world, but nothing makes him light up like consideration of his three extraordinarily handsome and winning children, two boys and a girl, who have often appeared in his prints.”2

In 1958 he toured in the USA at the invitation of the Japan Society and taught at the Pratt Institute. In 1963, Gordon Gilkey, head of the art department at Oregon State University in Corvallis, invited him to teach and work at the University. Using a translator, he taught an extension class at the University to a mostly young group of artists. "Gilkey pushed Sekino to experiment with new techniques and shared his vast personal collection of contemporary prints from around the world."3

During his 1963 stay in the U.S. he also taught at the University of Washington, worked at the Tamarind Studio in New Mexico, where he created several large lithographs, and studied with the artist Glen Alps (1914-1996), the inventor of collography.4 He returned to teach at Oregon State in 1969 and in 1975 his Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido Road series was shown at the University of Oregon Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art alongside the Museum’s collection of Hiroshige’s Tokaido prints. He visited France and Spain in 1976 and China in 1979.

In 1981 he was awarded the Purple Medal Ribbon by the Japanese Government. The following year, he had a solo exhibition at Central Museum Tokyo and in 1987 he was awarded the 4th class medal by the Japanese Imperial Household.

Along with Munakata and Onchi, Sekino credited the German painter and printmaker Albrecht Dürer (1471– 1528) with influencing his work saying, “I think my work has been influenced by Durer. One of the things I like most about him is his thoroughness, his corner-to-corner completeness.”5

Sekino studied printmaking techniques from books, and as a result surpassed many sosaku hanga artists in his ability to produce editions of consistent quality. Sekino’s printing prowess was such that he was “permitted to print fifty copies” of Onchi’s Portrait of Hagiwara Sakutaro in 1949, which was “unprecedented in Onchi’s work” up to that point.6 He also occasionally printed for Maekawa Senpan (1888-1960).

Sekino created over 400 prints during is lifetime.

Sources: "The Art of Sekino Jun'ichirō: Expressive Realism and Geometric Formalism" by John Fiorillo, appearing in Andon (The Journal of the Society for Japanese Arts), Autumn 2017, No. 104.

In discussing the artist's change from mostly self-printed works with low edition numbers to larger editions in response to his growing fame, Fiorillo quotes Elias Martin, collector and curator of Japanese prints, as follows:

As the market grew for sōsaku hanga and Sekino's popularity rose, he [opened] up his own studio [...] to produce work that kept up with the increase demand [...]. By the mid 1950s Sekino chose to focus primarily on design [and block carving] and to let his studio [...] produce his prints [..]. After achieving success in the late 1950s, Sekino decided to reprint, through his studio, many of his early designs that had become highly popular.... Once Sekino settled on studio printing, even his occasional self-printed works after 1955 tended to look like studio impressions.

Series

Like many Japanese artists Sekino often created series of prints. Among his later series are Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido, Collection of Aomori Folk Toys, Collection of Famous Japan Folk Toys, Old Capital, and Prints of the Narrow Road to the Deep North. He also contributed to the 1945 series, spearheaded by Onchi Koshiro, Scenes of Last Tokyo (Tokyo kaiko zue).

Collections

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Cleveland Museum of Art, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, New York Museum of Modern Art, Cincinnati Art Museum, Museum of Fine Art, Boston, Library of Congress, Los Angeles County Museum of Modern Art, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Art Institute Chicago, the British Museum, Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, University of Oregon and the Portland Art Museum among others.

1 "The Art of Sekino Jun'ichirō: Expressive Realism and Geometric Formalism" by John Fiorillo, appearing in Andon (The Journal of the Society for Japanese Arts), Autumn 2017, No. 104, p. 77.

1 Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints - The Early Years, Helen Merritt, University of Hawaii Press, 1998, p. 239.

2 Modern Japanese Prints: An Art Reborn, Oliver Statler, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1956, p. 65-66.

3 From an informational card on the artist written by Dr. Maribeth Graybill, Curator of Asian Art, Portland Art Museum

4 Martin Zambito Fine Art website http://martin-zambito.com/GLEN%20ALPS.html

5 Statler, Modern Japanese Prints, p. 63-64.

6 Guide to Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints: 1900-1975, Helen Merritt, University of Hawaii Press, 1992,

p. 133-134

- Lavenburg Collection of Japanese Prints

Jun'ichirō Sekino

53 records

Include records without images

About this artist