Nature, Time of Silence and Toward a New Magnetic Field. By Kijuro Yahagi 矢萩喜従郎, (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kijuro_Yahagi). Provided by Endō Susumu via Nagao Eiji of The Tolman Collection, Tokyo, 6-9-23 via email. hg.

Why did Endō Susumu begin to use natural materials in his creative activities?

Studying the process by which he introduced nature into his works is revealing of both his ideas and the world he is attempting to construct.

Nature is ordinarily a very broad term, but for Endō it means scenes of plants or trees. Earlier, Endō had used objects. They included man-made objects such as glass bottles, pencils, scissors. fluorescent light tubes and light bulbs, and natural objects such as eggs and rocks. They were either extremely simple and unornamented to begin with or were rendered simple by the removal of ornament.

Nature, in the sense of scenes of plants and trees, was first introduced in

1987. Once introduced, nature rapidly multiplied and took over. The change was so rapid that within a year Endō was dealing with nothing but nature.

Endō has discussed his motive for introducing nature into his works. He felt that dealing with nature produced a more complex world than was possible with objects. He realized he had started to seek greater complexity. In the process of introducing complexity, he became more drawn to nature. Another advantage to making nature the subject was the greater freedom it allowed, for example, with respect to color. Endō, who believes that even a work that is planned rationally requires an element of sensibility, felt that using objects as the subject matter tended to overemphasize the rational aspect of a work He also felt that dealing only with objects was apt to isolate him from the external world.

Endō's youthful experiences with nature and the clear memories he has of those experiences are key to understanding his work. He encountered three very different forms of nature as he was growing up. He was born in Yamanashi Prefecture, spent his school years from sixth grade to the third year of high school in Hokkaido, and then moved to Tokyo. Thus, he was given a valuable opportunity to encounter nature in various guises. He was fortunate in being able to nurture a sensibility to nature through experiences in Yamanashi Prefecture. which is located in the middle of Japan, and Hokkaido, which is the northernmost part of the country. He came to realize his sensibility to nature, and it is with that sensibility that he regards nature in any new guise, even today.

When I asked him, in order to better understand his perceptual world, what quality he valued or sought, Endō immediately answered, "A sense of transparency. To get a more precise fix on that sense of transparency. I then asked him which he preferred, dry or wet, and he responded interestingly that he liked both.

The answer was unexpected, but I believe the natural environments in Hokkaido and Yamanashi Prefecture that he encountered in his youth account for that. Nature in Hokkaido is dry, in the sense of being matter-of-fact and remote, while nature in Yamanashi is of a very different kind. Endō has assimilated them both to such an extent that he cannot choose between wet and dry.

Endō has always felt it important to take his own photographs and previously took pictures of objects indoors. As his susceptibility to nature increased, he began to go out into nature and to take photographs. The fact that he began taking photographs in the outside world, that is, in nature, is itself quite meaningful. He felt that he would not be able to experience new, unexpected encounters unless he actually placed himself in nature, and he felt that new encounters with nature would lead to new relationships.

Relationships is a keyword for Endō. Endō's experience visiting Finland illustrates what he means by new relationships. Nature in Finland was attractive at first glance, but on closer examination he discovered that human intervention had made it too orderly. He felt it was a man-made nature. Endō confessed he was unable to take many photographs there.

Endō began to use nature as a subject matter not only because he sought new encounters with nature but because he sought to dissolve the self. A constructed nature seemed too artificial and dispiriting. Endō obviously feels that a new relationship cannot be established unless the encounter is achieved without reserve and the self is dissolved. It is thus with some trepidation that he seeks out nature.

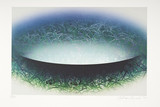

Once he enters the production stage, nature as captured in photographs is translated into the digital world of computers. Nature is reduced to points of light (ie. pictorial elements), and the work of production begins in which points of information are freely switched. Having committed to memory his aggressive venture into nature in search of a new relationship, Endō now eliminates all unnecessary elements in order to clarify that remembered relationship. He eliminates all that is unnecessary. but that does not mean he reduces things to pure forms, that is, to geometrical figures such as circles and squares. Though he may purify the subject material, the complexity of nature is never completely lost. The natural factor is always retained to the end.

Observing him engage in production work, one gets the impression that the aggressive spirit with which he encountered nature is somehow being put under lock and key. Yet it is precisely because he entered aggressively into a dialogue with nature that that is possible.

Without the tension that leads him to enter into an aggressive dialogue with nature and to discover a new self, the work would lack that crucial something. That crucial something is a time of silence, a stillness that is the exact opposite of aggressive dynamism. In that sense, the creation of that time of silence is both the criterion and motive for production.

Endō has made an extremely interesting remark: “A relationship means bearing the burden of time". Participation in a world with boundaries naturally demands the movement of the point of view, which is where time would seem to come into the picture. However, the time Endō is talking about is more interesting. in a space in which one is conscious of a new relationship, time flows in abundance, even if it seems to be a silent world in which time has stopped. What does that time of silence give rise to? I believe it is a poetic world with abstract and philosophical aspects. To enter into a time of silence is to take time to heighten one's spirituality, and that no doubt is what endows his work with a centripetal quality.

In his book, To the Extent that Sound and Silence Can Be Measured, composer Toru Takemitsu wrote that unless the silences between sounds are brought to the fore and made richer, sounds themselves lack luster. The book describes his innovative attempts to give silence greater substance. "To the extent that nature and silence can be measured” might serve as Endō’s credo. He weaves his images from a deep opposition to nature. He believes that without a time of silence, the sound of the wind and the murmurs of trees he was able to hear as a result of his resolute encounter with nature will not be sublimated and images and words will not emerge clearly.

Endō has previously mentioned his interest in the films of Tarkovsky. He has stated that he sensed in them an aesthetic of silence, and that they revealed a new and distinctive perception of time. Endō felt that Tarkovsky's interpretation of time was different from that of other directors. Endō no doubt sensed in Tarkovsky's films the presence of a world that floats between reality and unreality.

Endō’s world is created from a single photograph. It is not a world made by a collage of different photographs. Astonishingly, a world of ambivalent relationships that evokes in the observer opposing concepts such as spring and winter, day and night or life and death is generated by a single picture. It is not a world of parallel or sequential relationships. Instead, a single photograph produces an image in which reality and unreality simultaneously exist. Endō believes that with this approach a world of unreality can be made to well up, a world in which something entirely new can be discovered.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that the ampersand in "Space & Space” symbolizes the nature of the works by Endō of that title. The symbol "&” normally suggests a parallel or serial relationship. However, to Endō, it symbolizes a strange world of reversibility, a looking-glass world into which one has imperceptibly been drawn. Moreover, the ampersand signifies the boundaries of a space having all dimensions. There are some boundaries that are tightly closed, and others in which infiltration and dissolution exist. Endō clearly has in mind a world that comes into being when things are out of sync, when there is both continuity and discontinuity.

We need to take note of this special quality of the ampersand. Endō himself likes the fact that his work does not fit into any single dimension. His is a world, not of boundaries that can be indicated merely by the X and Y coordinates, but of three-dimensional boundaries that can only be explained by the introduction of Z coordinates. These boundaries are distinguished by a grand reversibility that at times permits a reversion from the next world to this world.

Endō’s interest in various boundaries and in the relationship between boundaries is a sign of his desire to explore new relationships. An interest in new relationships inevitably leads to a desire to generate a new quality of space. By a new quality of space, I mean a world of such exaltation as to make our hearts beat faster, a world that might be described as a pulsating magnetic field.

Will Endō continue to be a hunter who contains times of silence, resolutely introducing new relationships and interpretations of time, and exploring new qualities of space? That is the intriguing question.

Answers to questions provided by Nagao Eiji of The Tolman Collection, Tokyo, 3-9-23:

Endō-san started using digital media to create his works around that time of the earliest prints in LACMA's collection. He remembers that he started using a Macintosh computer in 1990 or so, after about a year of using software made in Israel. Therefore, it is correct to say that he was using digital media in 1992.

Susumu Endō

32 records

Include records without images

About this artist